Delisle Worrell is a member of the Board of Directors of CPSI and the Former Governor of the Central Bank of Barbados.

The story of the Barbados economy in the post-World War II period is one of successful development. What was in 1946 a desperately poor society with low life expectancy, high infant mortality, crowded and poorly maintained housing, and great disparities of wealth is today an emerging market economy with a human development index that is the highest in the Caribbean, and puts the country at Number 56 in the world, in the highest category of the UNDP's classification.

The story of the economy is also one of underperformance and squandering of much of the society's potential. It is a story of missed opportunities, lack of vision, and a failure to develop a body of thought that enriches global knowledge with insights that are unique to the experiences of small societies worldwide. The consequences have been especially harmful to economic policy.

Except for a brief moment in the late 1960s and early 1970s, economic policies in Barbados and the rest of the Caribbean have imitated those in advanced countries. Unsurprisingly, that has led to disappointing performance.

Essay Structure

This essay begins with a review of economic growth and macroeconomic stability in Barbados since 1946.

Investment is the engine of growth, adding to the capacity to produce and improve productivity; investment is the subject of the second section. That is followed by an analysis of fiscal policy and its impact on macroeconomic stability.

An important question is the extent of diversity in the goods and services produced in the country. We will see to what extent all the eggs are in one basket in the next section. As is widely recognized, the objective of economic growth is development; we will spend some time on the available measures of development and what they tell us about the material well-being of Barbadians.

We then move on to a discussion of Government policies and the extent of the Government's success in stimulating growth and development.

We end with an assessment of Barbados' economic performance, a discussion of what might have been done better, and some thoughts about future economic development in Barbados and the Caribbean.

Macroeconomic growth and stability

The phases of real economic growth that may be identified in Figure 1 are summarized in Table 1. The 1950s was a period of high growth, almost five percent annually, ending in 1963; the economy contracted in 1964, 1965, and 1967. There was a weak recovery in the early 1970s, with growth a little less than three percent per year, followed by another fall in output in 1974 and 1975. The recovery in the second half of the 1970s was stronger than in the sixties, matching the five percent per annum of two decades earlier. Once again, recession overtook the economy in 1981 and 1982. The subsequent recovery lasted until the end of that decade.

The years 1990-1992 were a period of balance of payments crisis and economic contraction, as emergency fiscal measures were taken to reduce domestic spending and imports in defense of the exchange rate peg. Renewed growth in 1993 petered out in 1999. An upswing in 2002 peaked in 2006 with a growth rate of nine percent. The impact of the Global Recession saw a contraction in 2009, and on this occasion, the economy stagnated for the rest of the period up to the present.

Figure 1.

Table 1. Growth, Investment, and Productivity

Instability, in a small open economy with a fixed exchange rate like Barbados, manifests itself in a loss of foreign reserves, which depletes the Central Bank’s war chest for defending the exchange rate and provokes capital flight.

Market perceptions of what constitutes an adequate store of foreign reserves have changed over time in Barbados. Up until the late 1980s, there was no apparent market apprehension about the exchange rate, even though, from time to time, foreign reserve levels were only 50 percent of the amount required to cover three months of imports, which became the norm following the 1991 balance of payments crisis (See Figure 2; the foreign reserves line is the ratio of actual reserves to the three (3) month cover). As we argue later, that reassurance was probably a reflection of the confidence afforded the market by the soundness of fiscal policy. Perceptions changed with the balance of payments crisis of 1991, the result of three successive years of deficits in the overall balance of external payments, which almost completely exhausted the Central Bank of Barbados’ stock of external assets.

The root cause of the problem was a persistent increase in Government spending, which provoked unsustainable levels of imports; strong fiscal correction in 1991 restored foreign reserve adequacy by the following year. Reserve levels remained healthy until 2010, when a precipitate decline started, eventually driving the economy into a balance of payments crisis again in 2018. The root cause, as in 1991, was fiscal: the failure to fully correct imbalances that had emerged as a consequence of the Global Recession.

Figure 2.

Investment and growth

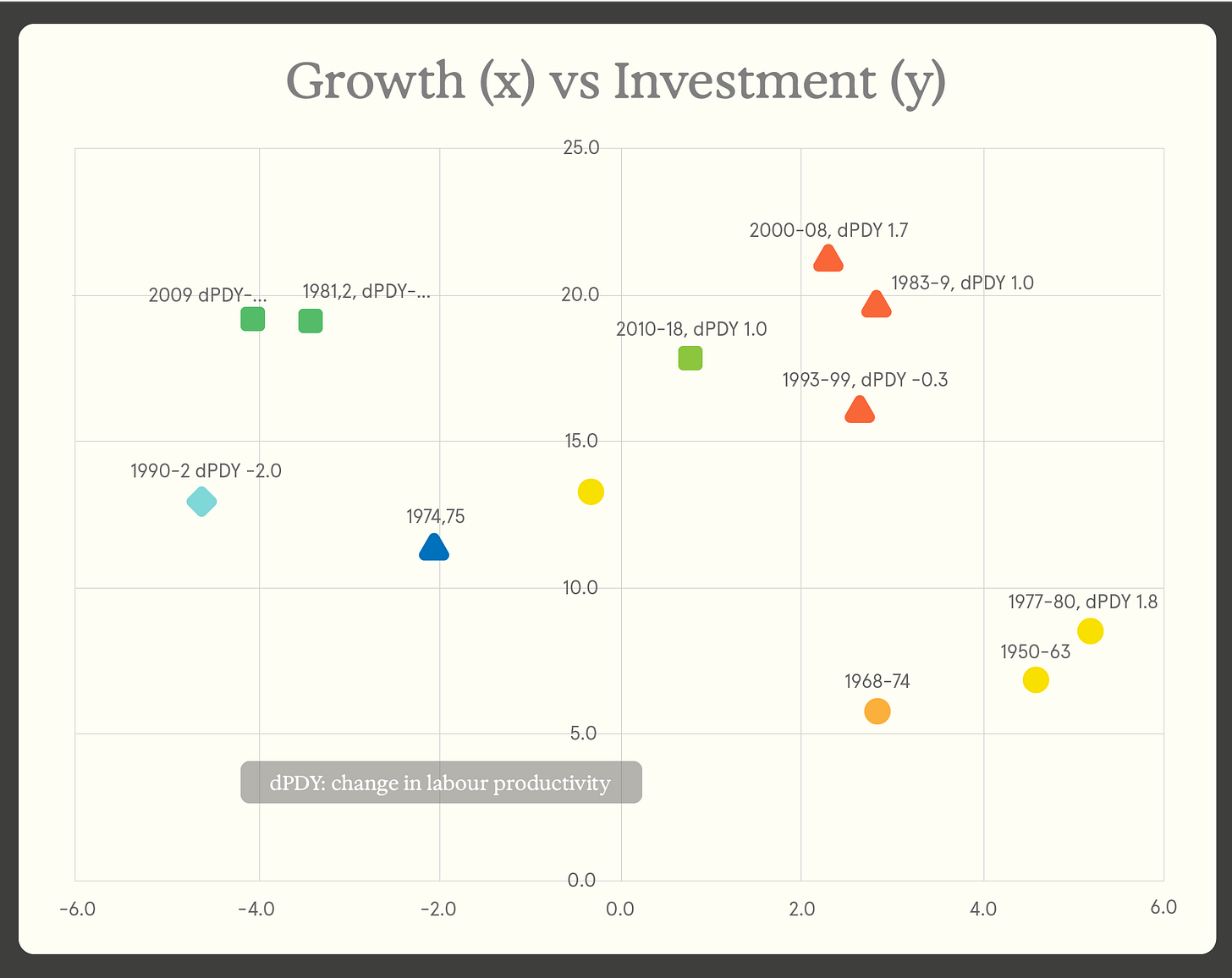

Table 1 shows the relationship between investment and growth during the various phases outlined earlier. In the periods of highest growth (the 1950s and 1977-80), investment was quite low, less than five percent of GDP; in the periods of highest investment (1983-89 and 2000-08), growth was only moderate, just over two percent. Investment reached almost 20 percent of GDP in the economic slumps of 1981-82 and 2009 and was recorded at 13 percent in the balance of payments crisis of 1991-92. This suggests that investment was much more productive in the first three decades from 1950 than it became thereafter. This thesis is borne out by other evidence that can be brought to bear.

Changes in productivity may indicate the efficiency of investment; productive investment in technology, skills, and organization can increase returns, creating an upward growth spiral of production and investment growth. Figure 3 captures the combined effects of growth, investment, and labour productivity for the periods where we have all the data. Investment seems to have been most efficient in this sense in the 1977-80 growth period, when growth averaged 5.2 percent, even though investment was only 8.5 percent of GDP on average; labour productivity in this period grew at an average of 1.8 percent per year. Much higher investment levels in the 1983-89 and 2000-08 growth periods yielded more modest growth rates of 2.8 percent and 2.3 percent, respectively.

That may be partly because the corresponding labour productivity growth rates were a little lower, at 1.7 percent and one percent per year for these periods. Furthermore, an average annual investment rate of 16 percent of GDP in the 1993-99 growth period was associated with an average growth rate of only 2.3 percent; that rate would probably have been higher but for the fact that labour productivity fell during that period, at an annual average of 0.3 percent. Since 2010 an investment ratio of 18 percent of GDP has contributed to anemic growth, averaging only 0.8 percent per year, with productivity increasing at an average annual rate of one percent. Labour productivity fell in all three crisis periods, by 1.9 percent in 1981-82, two percent in 1990-92, and 1.3 percent in 2009.

Other evidence of productivity growth in earlier years comes from Winston Cox, who showed that labour productivity in manufacturing grew by one-third between 1970 and 1979. In the same publication, I measured output per thousand employees at BDS$2.2 million in 1946, rising to $8 million in 1980 for the economy as a whole. A factor that would have contributed to the low productivity of investment in the 2000s was the fact that much of the surge in investment at that time was on account of a boom in foreign investment for the purchase of second homes in Barbados, in contrast to investment in manufacturing and tourism in earlier periods.

Figure 3.

Fiscal policy and macroeconomic stability

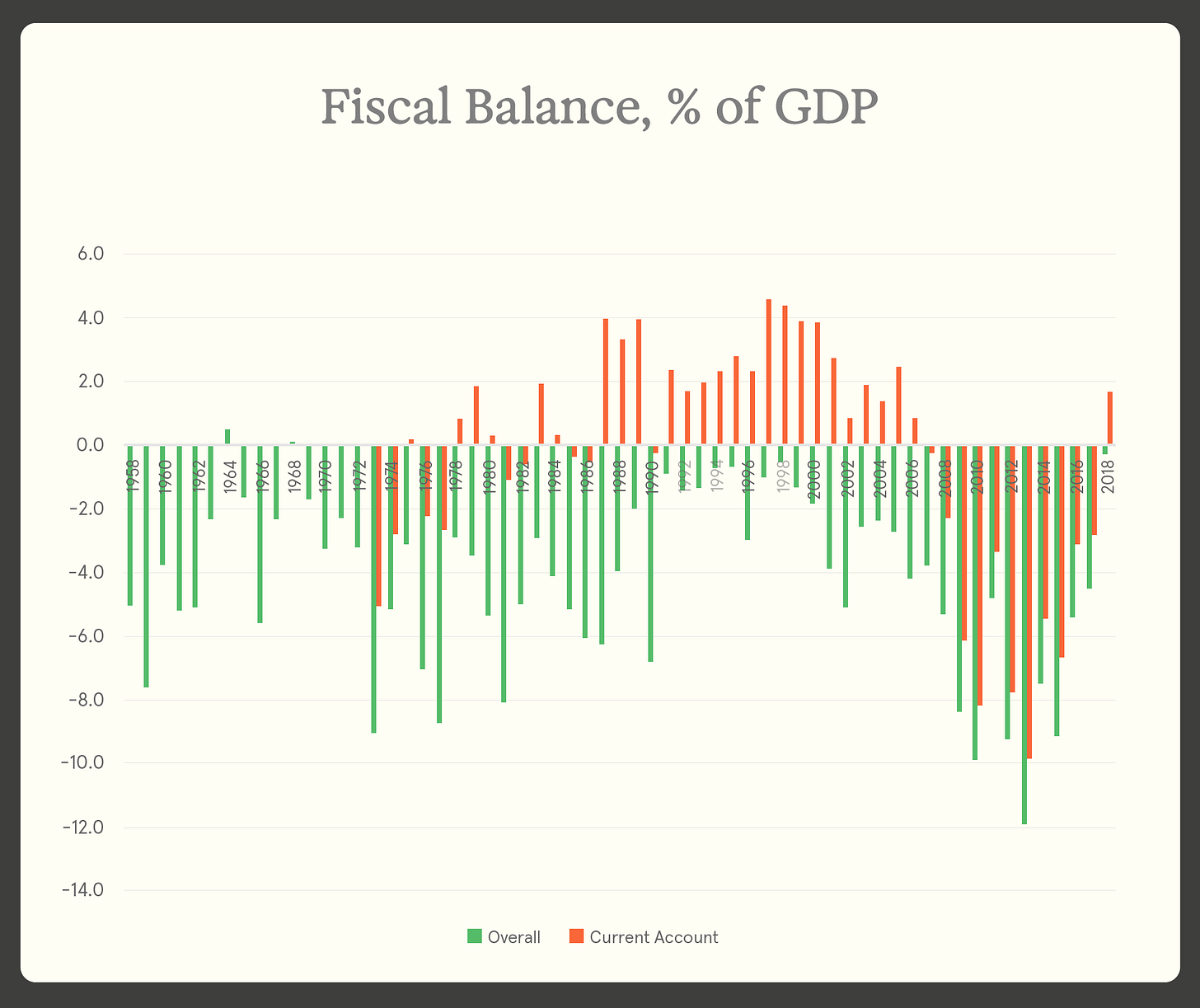

The election cycle heavily influenced Fiscal policy in Barbados: the overall deficit exceeded six percent of GDP in 1959, 1973, 1976 and 1977, 1981, 1986 and 1987, and 1990. Five of these eight large deficits occurred around the time of an election, in 1971, 1976, 1981, 1986, and 1991. In the years prior to Barbad’ first balance of payments crisis in 1991, large fiscal deficits were usually followed by corrective measures, bringing the overall deficit to four percent of GDP or less and restoring savings on the fiscal current account (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The economy suffered a major scare in the wake of the 1991 election when the expenditure stimulated by fiscal expansion caused a surge of imports that all but exhausted the Central Bank of Barbados’ foreign reserves and brought the country to the brink of a devaluation of the exchange rate.

A programme of deep cuts in the middle of the fiscal year restored the government’s current account surplus within the year, and the associated cutback in imports brought the balance of payments back into an overall surplus by 1992.

Financial support from the IMF helped to recharge the Central Bank's foreign reserves, which were 20 percent above the minimum of three months of imports by the end of 1992. Over the next two decades, it seemed that the lessons of the 1991 crisis had implanted in the social consciousness of Barbadians the crucial importance of maintaining surpluses on the current account of government’s operations and maintaining low overall deficits. For all of the 1990s and up until 2006 surpluses were maintained on the current account, and the overall deficit was contained to four percent of GDP or less.

However, the public memory proved unexpectedly short, as evidenced by the fallout of the Global Recession in 2008. The recession caused the collapse of the booming UK property market, which had fueled investment in properties in Barbados. The construction boom in Barbados was abruptly deflated, and foreign investment and government revenues fell sharply. The fiscal deficit was eight percent of GDP in 2009, rising to almost ten percent the following year, when the sudden death of the Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, David Thompson, left a vacuum in the leadership of the country and the management of its finances.

The new Minister of Finance, Chris Sinckler, tried to bring the situation under control and succeeded in reducing the deficit to five percent in 2011. However, with elections approaching in 2013, and with an unproven leader in Freundel Stuart, the temptation to prime the fiscal pump proved irresistible. Against the odds, Stuart narrowly won the 2013 election, but the fiscal deficit ballooned to a record 12 percent of GDP.

Over the next four years, the government made efforts to reduce the deficit, but they were never of the magnitude required, and by 2016, with another election looming, the deficit was still at five percent of GDP. Even more alarming, the Government’s current account by then had been in continuous deficit since 2008, with the excess of operating and financing expenses over revenue ranging between two and as much as ten percent (Figure 5). The relentless pressure of government deficit spending fueled consumption and imports, with no investment to stimulate improvements in competitiveness and additional foreign earnings.

The governing party held on to the bitter end, but with high debt, deteriorating creditworthiness, and plunging foreign reserves, a severe risk of exchange rate devaluation loomed. The incoming administration has gained a reprieve from devaluation with the help of finance from the IMF and other international financial lenders, with an adjustment programme that involves a combination of contraction of government expenditure, increased burden of taxation, and the repayment of old privately held debt on restructured, non-market terms.

Figure 5.

A comparison between the fiscal response to the balance of payments crisis of 1991 and the prolonged struggle to restore fiscal prudence in recent years is instructive. In 1991 the cut to the fiscal deficit was swift and decisive: the deficit of seven percent of GDP in 1990 was reduced to one percent in 1991, principally utilizing deep expenditure cuts, amounting to four percentage points of GDP. They included an across-the-board wage cut, together with a reduction in employment in the public sector. In contrast, more recently, expenditure has not been brought decisively under control, and this has made it more difficult to return the fiscal accounts to sustainability.

Government expenditure burgeoned from 33 percent of GDP in 2006 to 41 percent in 2013. Budget tightening in 2013 brought expenditure back down to 33 percent of GDP in a single year. However, revenue, which had been falling as a ratio to GDP since 2003, when the ratio was 33 percent, experienced a further sharp decline in 2013 and 2014, to only 26 percent of GDP by the end of the latter year. As a result, the 2014 deficit stayed stubbornly large, at 7.5 percent of GDP, despite the expenditure cuts.

The backlash against the expenditure correction induced the Government to relax some measures and abandon the reform of state-owned companies and other measures needed to achieve the targets of the fiscal correction. The ratio of expenditure to GDP rose in 2015, resulting in a worsening deficit despite the imposition of additional taxes. Tax increases and expenditure cuts in the next two years succeeded only in reducing the deficit from nine to five percent of GDP. By the end of 2018, the new Government’s IMF-supported adjustment programme had yet to take full effect, and the impact on expenditure was not yet apparent.

The Government’s wage bill remained at eight percent of GDP in 2018, not much changed from the previous year, and transfers to public enterprises had increased slightly, also to eight percent. The bulk of the reduction of four percentage points of GDP between 2017 and 2018 was contributed by cuts in interest paid to holders of domestic Government debt (two percentage points) and arrears of interest on foreign debt (one percentage point). Additional taxation contributed about one percentage point to closing the fiscal gap. (See Figure 4 and Table 2.)

Table 2.

Growth and structural change

Over the 1946-2018 period, the Barbados economy was transformed from dependence on sugar as the main engine of economic growth, with tourism a secondary source of foreign exchange, to today's tourism-dependent economy, with international business and financial services the secondary source of foreign earnings. Along the way, manufacturing rose to a level of importance almost equal to that of tourism by 1980, but manufacturing then suffered a long decline which has left it of minor importance in the economy.

Like all small open economies, Barbados specializes in exporting a limited range of internationally competitive goods and services, earning the foreign exchange to purchase internationally the wide range of products needed to sustain the modern economy. The competitiveness of exports attracts incoming investment which increases capacity and fuels growth and employment.

In the 1940s, the sugar industry was the main export, providing 55 percent of foreign currency inflows, followed by tourism. Sugar output grew significantly in the 1950s, with sales to the UK guaranteed at remunerative prices under the Commonwealth Sugar Agreement. Output peaked in 1957, and production averaged in the region of 200,000 tonnes per year until the late 1960s. By that time rising domestic production costs were undermining profitability in the industry, and output fell precipitously. By 1974 output had been reduced by half; in that year the CSA ended, to be replaced by the sugar protocols of the newly-formed Africa-Caribbean-Pacific (ACP) Group of countries trading with the European Union. The sugar industry never returned to profitability, and over the years since output and exports have declined to insignificance. (See Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Tourism and manufacturing both overtook sugar as the most important foreign exchange-earning activity in 1971. Tourism then entered a sustained growth period that lasted until 2004. By that time, foreign earnings from tourism were well in excess of the combined earnings from other services and manufacturing, the only other international earnings sources of any importance.

There was no overall increase in hotel accommodation in Barbados during this period; the increases in real value added in tourism were a result of the enhancement of the product, through the upgrading of hotels, the development of ancillary and support services, and the emergence of purchases of second homes as a significant source of foreign earnings.

The property market boom, which was a spillover of the UK pre-recession boom, came to an abrupt end in 2007, and tourism lost ground in this segment which it is yet to recover, over a decade later.

In the early 1980s, the Barbados economy was more diversified than it has been before or since. Tourism, the main driver, was closely followed by a manufacturing sector that exported garments, processed foods, electronics, household chemical products, and other items. The still-declining sugar industry remained a significant third pillar of the economy.

Manufacturing, which like agriculture benefited from Barbados' relatively low wages at the time, grew steadily over the preceding decades to a peak real value added in 1980. Soon thereafter, a one-third devaluation of the Trinidad and Tobago dollar against the US dollar reversed the comparative wage costs in Trinidad and Tobago and Barbados. Unskilled and semi-skilled labour was now much cheaper in that country, and Barbados lost its most important regional market for manufactured exports. This was followed, over the subsequent decades, by the loss of electronics and service suppliers to the US and other markets. Manufacturing declined until its contribution to GDP in 2018 was only one-third as large as tourism.

For about three decades, from the late 1970s, companies established in Barbados to provide business and financial services (IBFS) internationally made a significant contribution to foreign earnings and economic activity. Although incentives for the establishment of such companies were in place since the late 1960s, active promotion by the Government began only in 1976. By the early 1980s, this new sector's foreign earnings were over 40 percent of the earnings from tourism, which remained in the lead by a very wide margin.

Earnings from IBFS activities fell back to 30 percent of tourism receipts at the time of the 1991 balance of payments crisis. After slow recovery in the 1990s, the sector experienced a boom period from 2000-2010, when its contribution to foreign earnings was 50 percent of those from tourism. Sadly, the business case for locating services in Barbados has largely been eroded by tightening international regulations aimed at curbing money laundering and tax evasion by international companies; revenues from the IBFS sector have declined to one-fifth those of tourism, their level of the mid-1970s.

Development indicators

The most substantial gains in the quality of life for Barbadians were realized in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. In the 1940s Barbados already had achieved virtually full adult literacy, but in every other regard, the country was among the most wretched in the Caribbean. In the 1946 West Indian census, the life expectancy at birth was reported as 53 years for females and 49 years for males.

The country had a tiny middle class of artisans, teachers, policemen, and public workers, and a wealthy upper class of landowners, businessmen, and colonial administrators. The majority of the population lived in poverty, working on sugar plantations and doing unskilled manual labour. For many, there was a regular source of income only during the sugar harvest, which lasted for five months of the year. The inequality of income, which resulted, is reflected in the high GINI coefficient of 0.518 recorded in 1950.

The emergence of tourism and manufacturing in the 1960s and 1970s were major factors in transforming Barbados into an essentially middle-class society by the 1980s. Wages were significantly higher in tourism than in agriculture, and even though there was large seasonal variation in tourism, the degree of price and wage uncertainty was far less than in agriculture. An important contribution of the manufacturing sector was in providing jobs for the female labour force, which previously had few options other than agriculture and domestic service.

The universal emphasis on education which was a feature of Barbadian society reinforced the beneficial impact of economic diversification. The Government devoted resources to widening educational opportunities, and there was a strong response from the population.

In 1960 only eight percent of the population had a secondary education or better; by the mid-1990s that proportion had risen to 80 percent. The result was the emergence of a vibrant middle class of business professionals and skilled service providers.

In 1950, annual incomes per head in Barbados were no more than US$168; the great wealth disparity reflected in the high GINI coefficient translated into widespread poverty. A majority of the population lived in overcrowded conditions in houses in poor repair, with poor sanitation, no running water or electricity, and in indifferent health. Infant mortality rates were among the highest in the Caribbean.

A major transformation took place in the economy in the next three decades, and by 1980 the per capita income reached US$3,474 per year. What is more, that income was far more evenly spread across the population, with a GINI coefficient that had fallen to 0.356 by 1979. Life expectancy at birth rose dramatically in the 1950s and 60s, reaching 69 years in 1970. Over two-thirds of the labour force had secondary education in that year.

The income per head grew exceptionally fast in the 1980s (Figure 7; the data is shown in logarithmic form to accurately reflect rates of growth over time), providing households and government the wherewithal to consolidate the improvements in health, housing, and nutrition which were made in the previous two decades. Education had long been seen as the best tool of social mobility, and growing incomes enabled families to invest more in the education of their children. Permanent employment opportunities afforded improved diets and non-agricultural jobs offered more time for personal and household care.

With growing tax income, the government was able to widen educational access, particularly at the secondary level, provide affordable public housing, and establish a network of public health clinics. An effective nongovernmental agency promoted family planning with official support, and this, together with the growing middle class slowed population growth despite reduced infant mortality and longer life expectancy.

After 1980, social and material improvements were harder to come by: per capita GDP, which had increased nine-fold in the 13 years between 1967 and 1980, doubled over the next 13 years. Based on international purchasing power parities, GDP per capita in 2017 was two and a half times that in 1980. That compares with a twenty-fold increase to 1980. There was also further improvement in health conditions, with life expectancy at birth, increasing from 72 years in 1980 to 75 years in 2000.

Figure 7.

The social and economic transformation in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s contrasts with incremental gains made since. In the 1940s Barbados was an agricultural economy characterized by widespread poverty, poor health and sanitation, and inadequate housing, with unstable extended family relationships and overcrowding the norm. By 1980 Barbados had a more diversified mix of foreign earnings, led by tourism and manufacturing, with the declining sugar industry still of importance. A new and vibrant middle class had emerged with the resources to improve their material well-being.

New opportunities for women in manufacturing and year-round employment in non-agricultural activities helped to raise most of the working class out of poverty, and housing, health, and sanitation were now of good quality. In the subsequent decades, gains were made incrementally in all areas of human development. The Human Development Index for Barbados, which combines measures of GDP per capita on a PPP basis with indices for health and education, rose steadily from 0.732 in 1990 to 0.813 in 2018, leaving the country at #56 in the global rankings, one of two Caribbean countries listed as having "Very High" level of human development, the highest category.

Government policy, development, and macroeconomic stability

In this section, we discuss the ways in which Government policy affected economic growth, development, and macroeconomic stability. The significant ways in which the Government influences the economy are through the provision of social services and infrastructure, tax policy, fiscal incentives, and the legal and regulatory framework.

Government expenditure on public services

The government made major contributions to the availability and quality of public services during the period of greatest development gains (Figure 8). Spending on education topped the list from the 1950s, at almost three percent of GDP; by the 1970s that increased to seven percent, mainly reflective of the successful push to provide universal secondary education. Over the same period, spending on health services rose from around two percent of GDP to almost five percent, with the building of a new general hospital and a network of free primary care clinics, distributed across the island. Substantial spending on affordable housing was a major government thrust in the 1960s, expanding greatly on the earliest efforts in the 1950s. By the late 1970s, expenditure on housing had increased almost four-fold, to about two percent of GDP. Spending on pensions, personal transfers, and other miscellaneous social services rose steadily during this period, to about three percent of GDP by the late 1970s.

Figure 8.

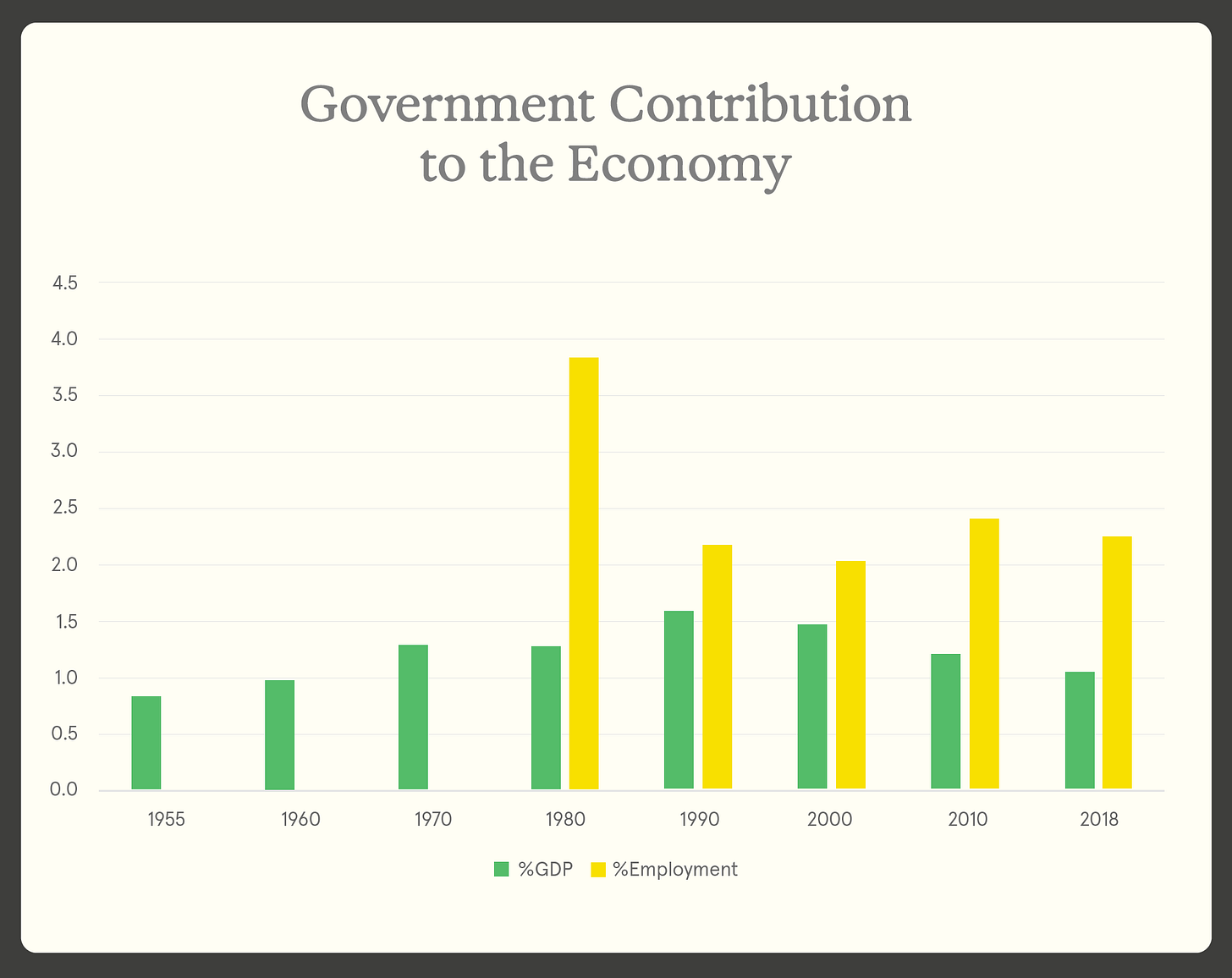

The Government’s rising importance in the economy appears to have had highly beneficial effects on development during this period. Government expenditure rose from about 25 percent of GDP in the early 1960s to about 35 percent in the late 1970s. Almost all of the expansion, relative to GDP, was accounted for by education, health, social services, and housing. What is equally important, the Government increased taxation relative to GDP, maintaining a small surplus on the current account, to contribute to capital expenditure. Government expenditure was productive, and prudent fiscal management maintained fiscal savings.

In contrast, Government spending since 1980 has had less obvious results. Most categories remained at around 1980 levels relative to GDP or a little lower.

The main factor pushing up education spending in the late 1990s was expenditure on the expansion of the local campus of The University of the West Indies, an effort which increased the number of persons graduating but may have adversely affected the quality of their education and the employability of their skills.

Spending on health, social services, and housing kept pace with GDP growth, more or less.

The Government’s contribution to overall economic activity declined steadily from 1990, from 16 percent to 10 percent in 2018. In contrast, already in 1990 Government provided employment for as much as 22 percent of the workforce; by 2018 the employment contribution remained the same, meaning that the share of Government jobs is now twice the Government's contribution to GDP. That disparity is even more disappointing in view of the technological revolution that has taken place over these three decades (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Overmanning and the decline in public sector productivity have been major factors in the decline in the quality and efficiency of public administration, recorded on the World Bank's Doing Business Reports and the annual Global Competitiveness Report (GCR) of the World Economic Forum.

The Barbados public sector is rated poorly in the processes affecting the establishment and operations of businesses, including trade and taxation. Major factors negatively affecting the island's competitiveness in the past decade included declining public trust in politicians, suspicion of social decisions, legal inefficiencies, wasteful government spending, and the burden of Government regulations, according to a recent GCR.

Tax policy

The most important single change in tax policy in Barbados was the introduction of a value-added tax (VAT) in 1997, to replace some indirect taxes previously collected, and to extend consumption taxes to services, which were not previously taxed. The rationale offered was to consolidate many previously disparate consumption taxes and simplify the collection system. The VAT failed in both those objectives: for various reasons, a number of levies and excises remain on the books, and the VAT has been plagued with arrears of payment and refunds by the tax authorities, errors, and disputes in calculating the value of services, and other difficulties.

The switch to the VAT worsened the tax system's impact on income distribution, increasing the relative burden on the lowest income groups. In the 1950s, taxes on goods and services, which are more burdensome on lower incomes, contributed no more than 14 percent of revenues.

The largest contribution at that time came from import duties, at about one-third of revenues (Figure 10). The progressive personal income tax contributed about 17 percent. Tax policy contributed to the improvement in the distribution of income in the 1960s and 1970s as the contribution of the personal tax rose to 27 percent of revenue by 1978.

Figure 10

A surge in consumption taxes and levies in the 1980s marked the beginning of a reversion to a tax system that put greater burdens on lower incomes. Goods and services taxes (not including import duties) reached 30 percent of total revenue in 1987. The impact of this shift would have been tempered by the effect of the income tax: Mascoll (1991) assessed the impact of the income tax in the 1980s, concluding that although the system shifted the burden somewhat against the middle class, the income tax system remained strongly progressive.

The introduction of the VAT has given a distinctively regressive bias to the overall tax system. In 2018 VAT accounted for 31 percent of revenues, twice the contribution from the personal income tax. What is more, a study by Boamah, Byron, and Maxwell (2006) found that the redistributive impact of the income tax had decreased between 1987 and 1999. The study has not been updated, but if that remains true, it aggravates the regressive impact of the increasing bias toward indirect taxes.

Capital expenditure

Capital expenditure was above two percent per annum of GDP and as high as six percent occasionally, right up to the time of the Global Recession (Figure 11). In most years, capital expenditure was funded, to a significant extent, from surpluses on the current account. In years of fiscal difficulty (1976-77, 1981-82, 1990), the government was dis-saved, having to borrow to close gaps between the current government spending and insufficient revenue. In all those cases fiscal correction in subsequent years restored a surplus on the current account. In the years from 2008 onwards, however, capital expenditure has averaged just two percent per year, and the Government has been obliged to fund such expenditure entirely by borrowing because current account deficits have been large.

Figure 11.

Not only has capital expenditure been lower in relation to overall activity, it has been less efficient. Maintenance of Government properties and facilities has been inadequate, and there were numerous examples of temporary closure or abandonment of schools and public buildings as a result. The partially- completed sewerage system failed in 2016, and plans for completion of the system and installation of modern sewerage treatment appear to have been abandoned. Insufficient investment in water sourcing, storage, and distribution has left parts of the island chronically short of potable water. Piecemeal and inconsistent maintenance of the road network has resulted in poor surfaces and a need for large investments in rehabilitation and upgrades.

There was also insufficient investment in the island's port and airport, critical bottlenecks in an economy where international trade, tourism, and international business are at the heart of all economic activity. Both port and airport are in need of major upgrades that would significantly reduce costs and improve throughput. What is more, Barbados may be missing out on possibilities for port and airport expansions to link to global transportation networks.

Barbados' geographic position, the easternmost of the Caribbean islands, gives it a natural advantage in providing a node for transportation links across the Atlantic, north and south to the Americas, and west to the Panama Canal. However, successive administrations in Barbados have shown no interest in partnering with international transportation companies to take advantage of this potential.

Government policy and changes in the structure of production

Government plans and policies for promoting production and economic diversification failed to bring lasting change at any time during this period. In the 1950s Government raised what for the time was a very large sterling bond to fund the construction of a deep water port, with modern facilities for the loading of sugar, then the economy's principal export. The port has proved to be an invaluable resource, except for the sugar industry, which went into decline within a decade of the port's completion. Although responsibility for the failure of the sugar industry has to remain with the lack of a practical vision and strategy on the part of industry leaders, the absence of a consistent land use policy, and the Government's wrong-headed financing of badly run farms over several decades, served to hasten sugar's demise.

The introduction of a special low-tax regime for international business and financial companies wishing to establish in Barbados to provide services worldwide was the most innovative Government policy action taken to open the way for new activities. From small beginnings in the 1970s, the IBFS sector grew rapidly in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with a contribution to foreign earnings and Government revenue second only to tourism. However, few companies established in the sector had operations in Barbados large enough to avoid the "tax haven" label, and the sector has suffered a decline under relentless pressure from EU and Canadian regulators.

The Government’s policies for improving social and public services and building infrastructure were arguably far more important for Barbados' competitiveness and attractiveness to investors than were other more targeted measures such as financing and incentives. The areas in which Barbados scores above the average for Latin America and the Caribbean in the Global Competitiveness Index are health, ICT adoption, skills, the financial system, and business dynamism, reflective of the quality of health and educational systems, and the country's open economy.

On the other hand, measures such as fiscal incentives to industry, Government funding of enterprise, and state enterprises have all failed to have a noticeable impact on what is produced and exported. My 1989 paper on the impact of tax incentives found a strong bias in favor of the purchase of agricultural machinery, at a time when agriculture was in decline; no bias in favor of tourism, the economy's mainstay; and a weak bias in favor of manufacturing, which had passed its peak.

The Barbados Development Bank and the Agricultural Development Bank both fell into insolvency. At the same time, the Barbados National Bank, the state-owned commercial bank, proved to be a less profitable and less efficient replica of the international commercial banks operating in Barbados until its eventual sale to Trinidad-Tobago's Republic Bank. The largest state-owned commercial enterprise ever attempted, a cement factory, never made a surplus and was soon sold to Caribbean investors. Miscellaneous programmes of finance, advice, and support for small and medium enterprises over many decades may have served some social purpose, but they made no impact on production or employment in the aggregate.

In the 1970s import tariffs, quotas and other restrictions were popular with Caribbean Governments, in Quixotic attempts to stimulate import substitution.

As I have shown, economies as small as those of the Caribbean have no hope of competitively supplying locally-produced vehicles, steel, fuels, staple foods, clothing, appliances, chemicals, building materials, and all the many and varied goods and services which a modern economy needs. The Barbados Government did fall for the temptation to promote domestic import substitution, and a handful of domestic companies depend on tariff protection. However, import substitution never made a significant contribution to output, and protective measures have largely been eliminated.

The quality and appropriateness of macroeconomic policy turned out to be the most influential factor with respect to the Government's impact on development outcomes. In my 1987 study of Caribbean economies, I said "Fiscal policy has been the cornerstone of programmes that maintained economic stability, and the downfall of those that aggravated disequilibria". That assessment was made on the basis of experience in the English-speaking Caribbean between 1970 and the mid-1980s. Barbados' experience since that time, discussed above, confirms that conclusion. In the 2019 GCI Barbados has fallen below the Latin America and Caribbean average for macroeconomic stability. The country ranked 59th of 141 countries in overall competitiveness but only a lowly 109th with respect to macroeconomic stability.

Government policy and economic development: an assessment

The Barbados economy suffers from a peculiar malaise: the country boasts a very high level of human development and a wealth of talent, but there is in the society a pervasive sense of lack of purpose and direction. The economy has been in the doldrums since the time of the Global Recession, and young people are looking abroad to make their lives and careers and improve their prospects. After achieving some success in diversifying sources of foreign earnings in the 1960s and 70s, the economy has reverted to depending for its dynamism solely on tourism. Agriculture has virtually crashed out as a foreign earner, the manufacturing sector is in slow long-term decline, and the international business and financial services sector is faltering.

The Government continues to burden the tourism sector, the economy’s only vibrant source of vital foreign earnings, with an ever heavier load of largely inappropriate taxation. Inconsistent policies and poor quality of regulation have deterred or delayed over US$1 billion in new hotel investment since 2016. Fiscal incentives that are poorly designed and inconsistently applied continue to distort the local tourism product away from Barbados' competitive strengths in high quality, low volume, heritage, cultural, and other niches, as opposed to high volume and cruise tourism, which carry the danger of overcrowding, environmental degradation and devaluation of the tourist experience.

Insufficient and inefficient public sector investment and maintenance is reflected in deteriorating roads, public transportation, sanitation, water supply, and other public services. Public sector performance is well below the international standards required to achieve an acceptable ranking in the Global Competitiveness Report and the Doing Business Report.

Government policy is still characterized by capricious decision-making, inconsistent regulation, poor data and statistical flows, lack of timely publication of annual reports, and failure to make good on commitments. The new economic strategy which has secured the financial support of international financial institutions has increased the tax burden and resulted in unplanned layoffs in the public sector.

The intellectual establishment, globally and in the Caribbean, has provided no new ideas for economic strategies for growth and development in small open economies like those of the region. The current recommendations, unchanged for four decades or more, are for domestic economic diversification and regional cooperation. Those recommendations fail to reflect today’s reality of a Caribbean nation and economy that transcends national boundaries and answers to no single sovereign. It comprises a network of social, familial, cultural, business, and economic connections and transactions that reach across the Caribbean and into the diaspora. The future development of the Barbadian economy depends on its contribution to the economic development of this Caribbean nation.

Barbadian prospects for material betterment appear very appealing when seen in this light. Already individuals and families, in Barbados and the rest of the Caribbean, are availing themselves of opportunities which the breadth and diversity of this Caribbean nation affords, through migration, remittances, purchase of retirement homes, charitable donations, business establishment, franchising, financial networks, working remotely, traveling for work, and in many other innovative ways. Governments, including the Government of Barbados, should reformulate national policy with a view to achieving progress in this regional context, to enhance the competitiveness and reputation of the Caribbean in the global market.

Conclusion and Recommendations

I conclude with some concrete suggestions for Government policy in Barbados that leverage the country’s competitiveness and potential, to ensure that the national space once again becomes a leading node of Caribbean development.

The Government would need to rework fiscal incentives to promote quality in tourism and discourage cruise and high-volume tourism. It would have to provide more financial support for culture, heritage, sports, and other tourism niches. All government support to private enterprise, including tourism, would be conditional on the achievement of mutually agreed performance targets.

The government would need to contract with the best international expertise to complete a three-year makeover of public services and administration, to bring government services to an acceptable international standard of performance, and to publish reports and statistics in a timely manner.

A practical, time-bound action plan for the complete replacement of fossil fuel sources of energy is essential, with an action plan and three-yearly deadlines to keep the strategy on course. Renewable energy has the potential, in time, to provide the economy with a sector that would make a contribution to GDP comparable to that of tourism.

Government incentives, legislation, and regulation would have to be used to refocus the international business and financial services sector away from tax planning, and towards providing services domestically that are directly linked into the global value chains of international companies.

The Government would need to form strategic partnerships with international transport firms for the development and management of the Bridgetown Port and the international airport, to provide major nodes in Barbados for international transport networks.

The education system would be upgraded to provide language skills from the earliest years of schooling, together with improved quality and familiarity with modern communications tools, consistent with the country’s outward orientation.

The domestic currency serves little purpose in an economy which is oriented to the outside world; it should be abolished, and the US dollar, which drives the economy both in terms of income and spending, should be used as legal tender.

Barbados’ legal and regulatory framework should be recast in support of a new regionalism that incorporates services networked across the Caribbean and the diaspora.

Barbadians and members of the Caribbean nation are securing their future and making a name for the Caribbean nation on the global scene. All told, including the diaspora, the Caribbean is a mere sliver of humanity, but the people, the culture, and the achievements of the region are legendary. The responsibility of our Governments is to find appropriate and creative ways to ensure the parallel development of regional governance through policy reform that reflects the realities of the twenty-first century and the possibilities that are opened up by new technologies.

DeLisle Worrell’s latest book, published in 2023, is titled “Development and Stabilization in Small Open Economies Theories and Evidence from Caribbean Experience”