Notes Towards Caribbean Dollarization (Part 1)

A multi-part series on why Caribbean countries should prioritize dollarization

Above is a tl;dr audio director’s cut. A quick behind-the-scenes chat about the main points of this article.

Currencies have failed across the Americas, from Jamaica to Venezuela - taking people's livelihoods with them. If these countries all used the U.S. dollar, it would be for their benefit. But unfortunately, dollarization diplomacy has lost its glitter. Moreover, there has been a recent increase of commentators and would-be experts proclaiming a new era of "de-dollarization." Tyler Cowen recently gave an excellent short discussion of why this "de-dollarization" sugar rush does not add up to much. Yet, another curious feature of this debate needs to be more explicit: it is predominantly an English language concern in the Americas.

There are few policy debates so fragmented by language as the dollarization policy. At least in Latin America (I live in Panama), if you search "la dolarización" (or other Spanish variants, dolarizar, etc) on any social media, you will see a very different debate space. If you search "dollarization," most results will be about the poorly-reasoned impending de-dollarization of the world. If you search la dolarización, you get results about the merits of dollarization and conversations on how to dollarize the economy.

Two main factors significantly contribute to this. Firstly, three countries in Latin America have officially dollarized: Panama, Ecuador, and El Salvador - along with others in the Caribbean. There is a strong sense that dollarization can be done, and it is not an esoteric theoretic debate. Secondly, the Presidential elections in Argentina are coming up this year, and a major candidate is campaigning on the dollarization policy.

Javier Milei, a current National Deputy for Buenos Aires, is campaigning that if he wins, his first significant policy will be to close the central bank and dollarize Argentina. Argentines have been suffering from increasing inflation, estimated to have reached 104%. A recent Econtalk podcast is a good discussion of this social issue in Argentina.

Every day, Milei posts videos on TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, etc., about the benefits and mechanics of dollarization. Every day all TV news stations in Argentina host panels and debates about dollarization, and universities host seminars. Economic policy commenters across social media make analysis videos, and online influencers do street interviews on dollarization. Of course, all in Spanish.

Dollarization is a likely outcome in Argentina in 2023. In the late 90s, Argentina raised the question of dollarization amid the chaos of the Asian financial crisis, the Mexican peso crisis, and the great depression of Argentina. This potential dollarization of Argentina reignited the discussion in Washington in 1999.

With these debates raving again in Argentina and so much recent overweening chatter in the U.S. about "de-dollarization," I think it is a great time to re-open this debate in the Caribbean.

This post is Part 1 of a planned multi-part series of notes explaining the benefits of Caribbean Dollarization and dissolving the relevant counterarguments. These public notes aim to compile the best arguments for a larger project. ¿Hay que dolarizar El Caribe?

Core argument: The structure of Caribbean economies is different in quantity and quality. Caribbean economies are import dependent. This is not a value judgment or a temporary state of affairs; it is an immutable fact of the world. Even the most basic economic activity, agriculture, requires tools made from metals not found in the Caribbean - they must be imported. This has been the state of the Caribbean from the beginning.

All imports are paid for using an international currency - usually U.S. dollars. There is no advantage for Caribbean countries to have their domestic currency; all domestic currencies in small economies are anachronistic. Caribbean countries should abandon their local currencies and adopt the U.S. dollar. The region's governments have uniformly abrogated their duties to design and implement credible macro-prudential policies leading to unjustified socio-economic degradation.

Properly construed, the current state of monetary affairs is a persistent abuse of power by governments to the detriment of Caribbean citizens. If Caribbean people used U.S. dollars as their sole currency, that would significantly expand their economic freedom and opportunities.

In essence, dollarization merely makes explicit what is already true: small open economies have a hard foreign currency constraint. It is not the so-called implementation of a straitjacket. The straitjacket has already been there.

I aim to build a wholistic case in favour of dollarization. And to do that mental models need to be constructed. In future posts in this series I will review the work done on this topic by Eric Helleiner for deeper analysis but for now let’s start from a simple position.

The Original Purpose of Local Currencies in the Caribbean

As I will repeat many times in future blogs, many characteristics of Caribbean economies have obvious colonial origins. Money, Currency, and monetary conflagrations are no exception.

Many readers will remember the Pirate of the Caribbean scene when the Brethren Court gathered to assemble the nine 'pieces of eight' originally used to bind the goddess Calypso to human form. In the film, these were nine random objects the first nine pirate lords of the first Brethren Court had on them at the time because they were "skint broke," i.e., they had no money.

The name of the objects was not chosen simply for comic relief. During this period of Caribbean history, the most common money used was the Spanish coin called 'El Real de a Ocho' (translated to English as 'Piece of Eight'). For centuries Spanish money was universally accepted in the Americas - the first universal New World currency before the British Sterling and long before the U.S. Dollar became a significant player.

A British diplomat, Baron Chalmers, in A History of Currency in the British Colonies published in 1893, wrote that "Barbados," and the West Indies (an older term for the Caribbean), "has always maintained a money of account different from that in actual circulation."

Baron Chalmers went on to explain:

“for some two centuries accounts were kept in [sterling], though the coins current were mainly Spanish; and at the present day, when sterling coins hold the field, mercantile accounts are kept in dollars and cents.”

During the early Colonial period, there was repeated political unrest concerning the state of the Currency within the Caribbean. This was because of a need for more usable Currency available for commerce in the colonies. A report from 1668 indicates a petition by the Colonists in Barbados for a mint to be established to create coins to be used on the island only "as in New England and elsewhere is practiced." Colonists and merchants in the Caribbean would often ship their coins back to the mainland for use there, leaving the islands with increasing demand for Currency but dwindling supply.

Another example is from Grenada (Colonial Act of 21st March 1787) ratifying the use of foreign coin:

Whereas by reason of the great scarcity of British silver coin in this colony, a certain foreign coin called a dollar and a certain piece of silver called a “Bitt”, like current money, have for the purpose of commerce and public convenience, been by general consent suffered to circulate and pass in payment.

Parliamentary documents during the early colonial period of the Caribbean are replete with complaints about the scarcity of Currency for commerce. The complaints decreased in the mid-1800s when merchants established banks, and these banking services fell some of the need for coins and cash as transactions could be settled with payment instruments at deposit at the bank (cheques, etc.).

But still too few people and companies had access to bank accounts.

To further alleviate the "scandal of currency," the new banks were given the right to print money on behalf of the crowns of the various Empires in the Caribbean. For example, few remember that Denmark had Caribbean colonies. The Danish West Indies islands were sold to the U.S. relatively recently, in 1917 to be renamed the U.S. Virgin Islands. The Danish West Indies National Bank still printed money with the Danish King featured until 1934.

This was a rare instance of a Danish monarch featured on the money of a U.S. territory.

Royal Bank of Canada began operations in 1864. In 1882, RBC chose the Caribbean (Bermuda) for its first international branch. At this time, the territories of what we now call Canada and the Caribbean were part of the more extensive British Empire and shared essentially the same world. RBC became a fixture of Caribbean commerce. If you visit the Bank of Canada museum, you will see currency notes from Barbados printed by the RBC on display. The one shown here is from 1938.

Surprisingly, the free banking period of the Caribbean has attracted very little attention from monetary history scholars. A lot more should be said about it, but the core point is that banking services tried to alleviate the real hindrance to commerce: the lack of available media of exchange. This was a valid reason for having local Currency fixed to Sterling.

Not even independence was sufficient to break fixed exchange rates with Sterling. DeLisle Worrell gives us a good analogy. The global currency system resembled systems of weights and measures like kilometers and kilograms. If you say 1 Meter = 100 Centimeters today and then tomorrow, say that 1 Meter = 110 Centimeters, does it change the actual physical length of the table you are measuring? No. That was the logic of fixed exchange rates of currencies.

Why the Caribbean lost its monetary credibility

In the British Caribbean, monetary policy was managed substantially by the British government in London. The British Government created special government departments called Currency Boards to manage the Currency of the colonies. Local currency notes and coins were issued with a fixed value of Sterling - creating little currency clones in the colonies.

So then, if the Currency Board issues £100 in local Currency, say in British Honduras (now called Belize), it kept an equivalent of £100 in Sterling in an account at the Bank of England. A 100% reserve of Sterling backed all local currencies. (In practice, it was slightly more than 100% reserves to withstand sudden shocks ).

The Currency Board's job was to ensure enough local media of exchange for everyday commerce and general payments. It was understood that the local Currency was merely a vehicle of trade - a convenience; it was not considered "real" money. Anything that needed to be purchased outside the local domain had to be bought in the underlying anchor currency accepted elsewhere in the Empire. These Currency Boards were highly effective. Throughout their existence, there were no balance of payments crises in the Caribbean. The technocrats in London ensured that the Empire's Caribbean colonies had stable money.

Caribbean countries continued Currency Board policy anchored to the Sterling until the 1970s. By this time, all major global currencies (including the Sterling) were measured against the U.S. Dollar, measured against a troy ounce of gold. But from the Smithsonian Agreement of 1971 (the Nixon Shock), the value of USD against gold was untethered.

By the late 1970s, the world had changed. Most of Caribbean commerce and trade was no longer tied to the U.K. Instead, the USA, and therefore dollars, became the leading trading partner. Since Sterling kept devaluing against USD, this caused economic shocks and inflationary pressure in the Caribbean. Caribbean money was still tied to the Sterling, so a devaluation of the Sterling against the USD was also a devaluation of the local currency against the USD. Caribbean countries began to switch their anchor currency to USD and abandoned the Sterling. If Currency Board-style policies with USD remained, less damage would have been done.

But we drifted into a Dark Age of monetary policy where fairy tales and fallacies displaced logic and historical facts about fixed exchange rates.

The commercial world of the Caribbean now looks different from what it did in the previous centuries. But we still talk about money as if we live in the 1800s. Most transactions are via debit/credit cards, bank wires, ACH transfers, and platforms like PayPal or Wise. We hardly use notes and coins in our daily lives; indeed, these instruments are only some of the primary means of payment.

Therefore the scarcity of these notes and coins is no longer an essential matter of national policy. We do not need to ensure sufficient notes and coins for circulation in a world where it is difficult to acquire such instruments. When people save money, they primarily save money in a bank account, not by accumulating cash notes. And that "money" in the bank account is merely a ledger entry in a digital database. This digital ledger entry can be rendered and presented in any form. You can call it Barbados Dollars, or you can call it United States Dollars, or you can call it Swiss Cheese Alpha Ten. The name you choose is immaterial to the digitally displayed numeric ledger entries.

The fact that we have banking ledger entries in the modern Caribbean denominated in anything besides a global currency like USD is an anachronism.

Why Size Matters

The idea of being resource "self-sufficient" is a nonstarter for the Caribbean. Barbados' local currency is only valid in the 166 square miles of the country. For every other square mile on earth, a foreign money has to be used - primarily USD.

I understand the urge to place all countries on equal footing globally, but this only distorts sound reasoning. It would be seen as absurd if every city in the US had its currency (with varying exchange rates) for use solely in those individual jurisdictions.

If there is no inflow of foreign currency into Barbados, then the country (and people) will be unable to acquire the means to live and strive - no medicine, no tech products, no clothes, no building materials, etc. Small economies are not import dependent because of some mismanagement by the government. They are import dependent because that is how they structurally exist.

As was pointed out by economists since the 1960s, the economic growth equation for the Caribbean can and should be restated. In a stylized way, you can proxy growth via GDP:

GDP (Y) = C (Consumer Spending) + I (Investment) + G (Government Spending) + [E(Exports) - M (Imports)]

But in small, very open economies, it is better to restate it this way:

Y + M = C + I + G + E

So important are imported goods to the growth and well-being of small open economies like the Caribbean that it cannot be an independent variable.

Why Devaluation Only Worsens Inequality

A common argument as to why small countries like those of the Caribbean should keep a local currency is the supposed benefits of potential devaluation to boost growth in the tourism sector. The original argument was that devaluation (against USD) would boost exports. But most Caribbean economies are primarily (more than 80% GDP) based on services. Since the tradable sector is so insignificant, the argument was switched to non-tradable promotion.

The idea is that devaluing the local currency against USD will attract more tourists to the country because they will see it as a "better deal."

There is a profound information asymmetry regarding how much the tourism sector (the largest non-tradable sector) is already dollarized. If you want to book almost anything in the Caribbean within the general tourist industry, you will see that all prices are already quoted in U.S Dollars.

Above are screenshots from the website of popular hotels in three Caribbean countries. The rooms are priced in USD. Even if you devalue the currency against USD, nothing will change in the prices of the tourism industry's primary consumption products/services. The plane tickets, the hotels, most restaurants, the taxis, etc., are all quoted in USD.

In reality, the only effect of devaluation is that workers will now be worse off because their wages will have a decreased purchasing power. Let me make this point more explicit.

As discussed above, even essential elements of life must be imported into the Caribbean, and the imports are invoiced and paid for in USD.

Suppose that today the exchange rate is 2 Barbados Dollars (BBD) = 1 USD, but a devaluation happens, and the rate changes to 4 BBD = 1 USD.

Wages are usually sticky because they lag (often severely by years) through abrupt economic adjustments. So a worker makes 1000 BBD per month, before and after the devaluation.

She paid 50 BBD for a weekly supermarket basket before and now pays 100 BBD for the same basket. She is absolutely worse off after the devaluation.

At the same time, the General Manager of the hotel she works at gets paid his salary in USD. After the devaluation of the local currency, he does not see an effect on his weekly shopping. Before, he would spend 100 USD on his supermarket basket; after, he also pays 100 USD. He is no worse off.

Indeed the most under-discussed element of devaluation is that it increases the inequality between the more affluent people (who usually have their money in USD) and the poorer people who work wage jobs for local currency.

Why Small Economies Never Had Monetary Policy Autonomy

Another argument in favor of keeping local currencies is the idea that governments of small open economies should maintain the option of having an independent monetary policy. But this does not cohere with the world as it is.

Small economies are different. Caribbean countries are dependent on foreign currency for imports and for servicing foreign debt obligations. We discussed the imports part already.

If Caribbean governments need to finance large projects, they generally need to borrow the money. They could try to borrow local currency from themselves or local institutions, but that won’t work unless they can exchange it for foreign currency to purchase the imports necessary for the project.

They could try to borrow foreign currency from banks based in the country, but they often need more spare foreign capital to lend large amounts. So then, the next option is to borrow from international markets (private lenders) or a multinational agency like the World Bank or China Ex-Im.

If the money is borrowed from private lenders, this is usually done via a bond offering denominated in USD. Because the Caribbean government wants USD and because the private lenders have no interest in taking the risk of investment in the local illiquid currency of a small government.

In either case, the money is borrowed in foreign currency, typically USD. This loan must then be repaid in USD - creating a foreign currency debt obligation.

The Caribbean government must ensure a sufficient inflow and stock of foreign currency to pay its debts. And the banking institutions need to maintain an adequate float of foreign currency to finance imports, which is a delicate balancing act.

Caribbean governments cannot (should not) hold too much money in foreign currency reserves. These USD reserves are just securities purchased from the U.S. Treasury, which means that small Caribbean countries provide constant loans to the U.S. government. If those reserves are too large, then this is an unjust decision, as what would be the point of loaning money to the U.S. government instead of using that money for projects at home?

But if too little money is held in reserves, then sudden shocks could cause currency mismatch problems and lead to a Balance of Payments crisis. Unfortunately, this has occurred repeatedly in the Caribbean since Independence.

These Balance of Payments crises have been exacerbated by the fact that Caribbean governments cannot resist the urge to finance domestic projects by artificially creating excess money in the local economy. When you create excess money in local currency without a corresponding increase in foreign currency, eventually, the problem metastasizes.

Small open economies are particularly fragile to Balance of Payments crises, even from mundane origins.

A stylized example will be helpful.

Suppose that Sandra, an entrepreneur, starts a new bakery in Barbados. She received a loan from a local bank (banks create loans out of nothing) in local currency. Sandra then needs to import new baking equipment from Miami. To do this, she converts the new local currency into USD at the bank. But for whatever reason, the bank does not have sufficient USD to give her. That’s no problem. The bank requests some extra USD from the Central Bank to fulfill Sandra’s request. Now suppose thousands more requests like this are sent to the Central Bank. The Central Bank cannot meet all of these requests because it cannot use up all its limited USD, so it announces a restriction on how much USD you can get annually. (This is called capital control. Barbados does have capital controls on foreign currency to this day).

Now, Sandra started her bakery and hired five new employees, all paid in local currency. These employees want to spend their salaries buying goods on Amazon. Their credit cards are denominated in local currency, so the bank needs to convert the local currency into USD to make transactions. But these employees are not earning any foreign currency, and therefore no correspondent inflow of foreign currency is occurring to match this new outflow. By starting a new business in Barbados, Sandra has become a drain on the economy. Her local bakery is not earning foreign exchange but is increasingly using it.

This scenario is the perverse nature of small open economies with local currencies under balance of payments constraints. Either you restrict the freedom of people to consume internationally via capital controls, or you roll the dice and end up in persistent crises with ever-devaluing local currencies. Worse yet is that both can happen concurrently.

Another argument favoring local currencies is the perceived ability to target domestic inflation. But this is impossible in small, very open economies because inflation is primarily imported. Increasing the domestic interest rate has, at best, a trivial effect on inflation since the prices of most goods are not set domestically.

When economies import their energy/fuel and the vast majority of food goods from outside the country (priced in USD), they are solely a price taker of foreign suppliers.

The small importing country has to accept whatever the price level is in the exporting country. The small economies of the Caribbean do not affect the price that suppliers in larger countries export their products for. Said differently, the prices in the Caribbean are strictly a function of the import price, and no interest rate policy can change this fact.

Moreover, inflation will also be exacerbated by the devaluation of local currencies. As stated above, the price of goods is a function of the import price. When the value of a local currency depreciates, the general price of everything increases. This is wholly undesirable and should be avoided.

The argument that small, very open economies had an independent monetary policy through the existence of local currencies does not match reality. Standard textbook macroeconomic models are often misspecified for small economies. Monetary policy could have never been used for economic adjustment, and fiscal policy is the only viable option for structural adjustment in the Caribbean.

Why Floating Rates Hurt Small Countries

At this point, it is helpful to distinguish between fixed, pegged, and floating exchange rates. Steve Hanke, a long-time champion of dollarization, wrote an instructive article explaining why most people (and indeed most Economists) misunderstand the nature of exchange rate mechanisms.

Hanke explains that most people interpret Milton Friedman's view on exchange mechanisms incorrectly - leading to the erroneous interpretation that Friedman was a dogmatic promoter of floating exchange rates. Friedman insisted that the dichotomy of fixed vs. float should be adjusted to a trichotomy: fixed vs. float vs. pegged. In his view, pegged and fixed are not synonymous as their function and results differ dramatically (as the above table summarises).

To quote Hanke at length:

“With a floating rate, a central bank sets a monetary policy but has no exchange‐rate policy—the exchange rate is on autopilot. In consequence, the monetary base is determined domestically by a central bank. With a fixed rate, or what Friedman often referred to as a unified currency, there are two possibilities: either a currency board sets the exchange rate, but has no monetary policy—the money supply is on autopilot—or a country is “dollarized” and uses a foreign currency as its own. In consequence, under a fixed‐rate regime, a country’s monetary base is determined by the balance of payments, moving in a one‐to‐one correspondence with changes in its foreign reserves.”

Continuing…

“Pegged rates. Most economists use “fixed” and “pegged” as interchangeable or nearly interchangeable terms for exchange rates. Friedman, however, saw them as “superficially similar but basically very different exchange‐rate arrangements.“For him, pegged‐rate systems are those where the monetary authorities are aiming for more than one target at a time. They often employ exchange controls and are not free‐market mechanisms for international balance‐ of‐payments adjustments. Pegged exchange rates are inherently disequilibrium systems, lacking an automatic response mechanism to produce balance‐ of‐payments adjustments. Pegged rates require a central bank to manage both the exchange rate and monetary policy. With a pegged rate, the monetary base contains both domestic and foreign components.”

What Friedman was trying to emphasize was the idea that a country's preferred exchange rate optimizes market-oriented adjustment. Hanke quotes Friedman explicitly stating that a fixed exchange rate is often preferred for developing countries:

“The great advantage of a unified currency [fixed exchange rate] is that it limits the possibility of governmental intervention. The reason why I regard a floating rate as second best for such a country is because it leaves a much larger scope for governmental intervention … I would say you should have a unified currency as the best solution, with a floating rate as a second‐best solution and a pegged rate as very much worse than either. - Milton Friedman (Money and Development)”

I stated above that currency clones (fixed exchange rates) have been the historical norm in the Caribbean until independence and the creation of new Central Banks. The choice of exchange rate framework was meant to be fixed, but most Caribbean countries have drifted away from this. The main reason is that governments are constantly tempted to perform monetary financing if they have local currencies. Of course, this makes short-term political sense. Spend more money now, win votes - it does not matter if it is unsustainable; that is a problem for the vague future. The world is replete with examples like this.

What was originally a system of fixed exchange rates to a global anchor became a patchwork of chaotic weak pegs. Governments and multinational agencies like the IMF try to make monetary policy do what it cannot do in small economies. This fiscal-ladenness of monetary policy has only produced ruinous results across the Caribbean.

In a recent book, Development and Stabilization in Small Open Economies (2023), DeLisle Worrell, the former Governor of the Central Bank of Barbados, rigorously examines the theoretical assumptions and empirical results of structural adjustments across the Caribbean. He states emphatically that:

“... the notion of an equilibrium value of the exchange rate which balances the demand and supply for foreign exchange, and the use of the exchange rate tool to stimulate growth, are notions which have no currency in the region. Both theory and experience attest to the difficulty of managing the rate, the dire consequences of allowing the foreign currency market to seek a rate that clears the market, and the futility of using devaluation as a tool to stimulate exports and growth in the SOE [small open economy].”

There is no rigorous theoretical, empirical, historical or practical reason for small economies in the Caribbean to prefer floating exchange rates over sound fixed exchange rates. And to go further, the optimal fixed exchange rate (or unified currency) is to adopt the U.S dollar.

Why there is no Loss of Economic Sovereignty

A persistent objection to dollarization concerns the idea that the U.S. government will have increased control of the foreign country if it dollarizes. This argument is particularly odd, especially in the Caribbean. But we need to discuss it.

There is this sense that monetary policy (even broadly conceived) is an element of sovereignty that countries can utilize at their discretion. As discussed previously, this has never been true for small countries. On the contrary, misuse and abuse of monetary policy have been one of the ways that small countries have gotten themselves into successive balance of payments crises and found themselves engulfed in IMF programs. These programs come with extensive conditionalities that, in many ways, strip sovereignty away from the country. Dollarization avoids balance of payments crises, rendering such rigid IMF programs unnecessary.

Another argument follows the line that the U.S. government can put more (vague) pressure on a country if it is dollarized. Strictly what mechanism would be used in this instance is still being determined. But suppose this can manifest in the U.S. government (potentially) pressuring a foreign country by threatening to cut it off from the U.S. banking system. The argument can proceed in that if USD is the only option a country uses, it can be swiftly cut off from the U.S. banking system. This existential threat gives the U.S. government more supposed control over the country.

However, This scenario does not consider that the U.S. government already has the ability to do this even if a country is not dollarized. In a detailed article published in Lawfare, the authors explain how the Patriot Act and the newer Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 “preserves the government’s ability to issue a financial “death penalty” to foreign banks … by restricting access to the U.S. financial system.”

For this mechanism to be triggered, the foreign bank must have a correspondent banking relationship with a U.S. bank. The foreign bank need not have a branch in the U.S., need to denominate its portfolio in USD, nor does its home country have to use USD. This law was used to sanction North Korean and Hong Kong-based banks.

Moreover, even without direct government involvement, U.S. banks can unilaterally damage small economies by cutting their banks out from correspondent banking relationships (a process known as “de-risking”).

Why Caribbean Central Banks have never been Lenders of Last Resort

The most frequent objection to dollarization from more sophisticated observers is the removal of the domestic central bank's lender of last-resort function. In a crisis, the central bank should be able to provide liquidity to banks (and sometimes other financial institutions) by creating new money.

As stated explicitly by Jeanette R Semeleer, then President of the Central Bank of Aruba, in a 2009 speech:

Some of the tasks of the central bank, especially the function of lender of last resort, which is the credit line for local banks when experiencing financial stress, will disappear. This is typically linked to the ability of the central bank to print its country’s currency.

It is a seductive argument because it feels so intuitively correct. The problem, however, is that it's just not true. Even with domestic currencies, Central Banks in small open economies cannot act as lenders of last resort (LOLR).

As discussed previously, nearly all goods and most inputs to production are imported into the Caribbean, and the domestic currency is only as good as the imports it can purchase. A point often sidelined in this question of LOLR utility is that small economies usually need dollars to anchor their domestic currencies in both regular times and in times of crisis. This is why, inevitably, in small open economies (and developing countries generally), financial crises are precipitated by currency crises.

Bank runs have a different effect in countries with currencies without international value. In the U.S., for example, if there is a run on a bank, people withdraw the money to put it in another U.S. bank or try to hold the money in cash. But in a country like the Dominican Republic, the currency is what people are trying to run from. They will take the money from the bank and immediately try to convert that domestic currency into USD or another real asset. They do not hold on to the domestic currency.

The massive dash by people to sell off their domestic currency holdings often results in rapid inflation (by buying anything they think will be stable value) and dwindling of dollar reserves (by converting to USD). If the government of a small economy issues domestic currency in this situation, it will only cause a quicker spiral. Manuel Hinds said in his book, "the main fear of the population is the loss through devaluation, rather than the loss of bank failures."

As seen repeatedly, governments that get into these spirals try to prioritize currency stabilization before anything else. And the only way to do this is to borrow dollars, which usually leads these governments to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

There is a genre of music in the Caribbean referred to as Social Commentary Calypso. Singers perform songs about issues affecting society spanning all themes from political squabbles to economic problems to the lack of religion among young people. It is a highly sophisticated genre of music that is generally unknown outside of the region. A song titled 'IMF Take Over' released in the early 1990s by a Barbadian calypso artist (stage) named Ras Iley is a splendid example of the role of the IMF during an economic crisis that occurred in Barbados at the time of the song's release.

First Verse:

We were warned,

but we didn't take heed.

Now the money gone,

all because of our greed.

Off to Washington,

scared as hell you run.

Put this blessed land,

Straight in de IMF hand …

Chorus:

Oh Mama, look what de devil do. (IMF take ova’)

Trinidad and Jamaica too. (IMF take ova’)

Their only aim is to devalue (IMF take ova’)

They don’t care about me and you (IMF take ova’)

They cut we by we throat,

We hanging on a rope,

I wonda’ when I go recover,

Because the IMF take ova’ …

Since Central Banks cannot stabilize the currency if they do not have sufficient reserves (again, usually USD), they need to borrow dollars. For a country in crisis, it is nearly impossible to borrow on international markets, so they turn to the IMF for urgent dollar liquidity injections. But the IMF only does emergency lending with strict conditionalities that the borrowing governments need to agree to perform. These involve various rigid fiscal adjustments like rapidly reducing government transfers and monetary adjustments like currency devaluations (which don’t work as previously discussed).

Ras Iley understood the reality. Washington (HQ of the IMF) is the backstop of the Caribbean economy in crisis, not the local central bank. The actual Lender of Last Resort in the Caribbean is the IMF (with dollars). Caribbean countries have been under seemingly perpetual IMF programs since the 1970s. (In a future post, I will explain why IMF programs are the real “dept traps” in the Caribbean. The problem is worse because the IMF and Caribbean governments are equally to blame.) The fact is that Caribbean countries have central banks (and therefore domestic currencies) is the raison d’etre of why the balance of payments crises occur. If the Caribbean country used dollars domestically and internationally, there would be no currency mismatch because every transaction would be in the same currency.

There would be no instance of a currency crisis precipitating a financial crisis because the currency people can access already the anchor currency. There can be no run on an anchor currency as there is nothing better to convert it into. So the advantage of having a central bank in the Caribbean to perform the lender of last resort functions is wholly illusory.

Moreover, having a central bank would make it more challenging to borrow money internationally during a liquidity crunch in the country’s banking sector. Take Panama (a fully dollarized country), for example. Bank assets and liabilities are denominated in USD. If a local bank has a liquidity constraint (actually rare in Panama), it can borrow from a bank anywhere in the world that lends in dollars by offering a more attractive interest rate. Because Panama’s financial sector is so well integrated with international financial markets (with sophisticated regulation examiners), the concept holds that liquidity can flow to where it offers the best risk-adjusted returns. This is not the case in Jamaica, where most banks are not well financially integrated and have books denominated in local currency, which presents many levels of risk for international lenders.

The elegance of a dollarized small economy with international financial integration is that in times of liquidity crunches, it is small enough that the extremely deep international dollar market can infinitely quench its borrowing thirst.

Should Any Caribbean Countries Not Dollarize?

You may be wondering if any Caribbean countries should not dollarize. In answering the question is essential to make explicit that “dollarization” is a subset of the general concept of “currency substitution.” That is, when Estonia abandoned the kroon to join to Eurozone, it effectively “dollarized” (substituted its currency entirely for another one) but with the Euro. So there are two questions to answer in this section. First, is there any Caribbean that should not substitute its domestic currency? Second, is there any Caribbean that should substitute its domestic currency for another one besides the dollar?

The Dutch

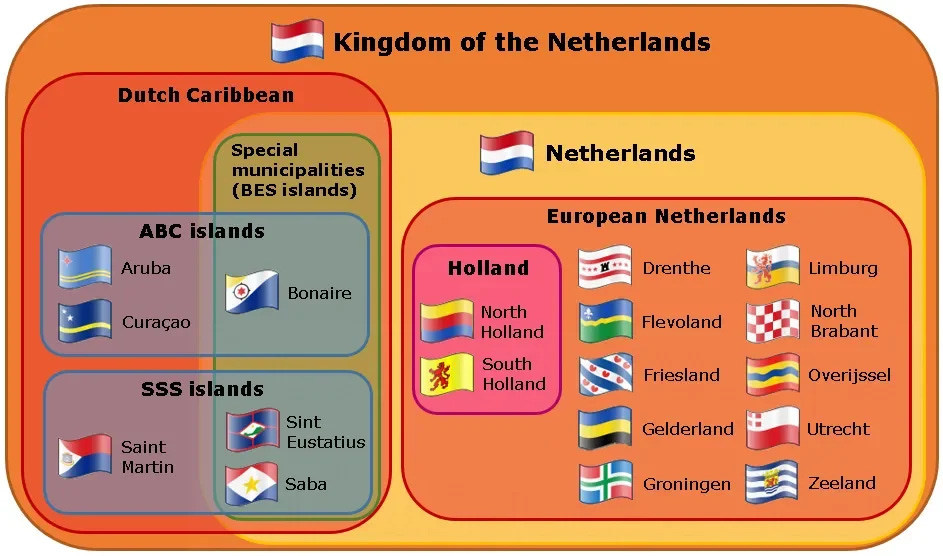

Let’s use the Dutch Caribbean to think about these questions. Since the colonial period, The Netherlands has extended beyond continental Europe to the Caribbean. There are two groups of countries falling into this category:

The CAS Islands: Curaçao, Aruba, and Sint Maarten

The BES Islands: Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba

This grouping may be confusing to wrap your head around initially. But the CAS Islands are part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands but are not part of the Netherlands (as a country). In contrast, the BES Islands are not overseas territories of the Kingdom but instead “public bodies” (think of them as municipalities) of the country of the Netherlands.

A chart should help with this explanation:

Essentially, the CAS Islands have more political and economic autonomy than the BES Islands while all remain effectively Dutch states. One other political/geographical point to note before I can move on is that the Dutch territory of Sint Maarten is one-half of a Caribbean island co-owned by France.

Both sides of the island are called St. Martin (with different spellings), and the entire island is also called St. Martin (yes, I know what you are thinking). The other similar example is the Caribbean island of Hispaniola (divided into Haiti and the Dominican Republic).

In any case, the point of making these references is understanding the odd nature of currency composition, even in this subset of the Caribbean. I said that the BES Islands (Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba) are effectively municipalities of the country of the Netherlands. For intuitive simplicity, think of them structurally as towns in the province of Holland. People born in the BES islands are European citizens. It would be intuitive to believe they used to Euro. But they do not. Since 2011 the BES islands have been using the USD as the sole currency.

The decision to dollarize was made out of convenience. Tourism is the most significant industry, primarily composed of U.S. visitors, And most of the trade is priced in USD. Also, the previous currency (before 2011) was the Netherland Antilles Guilder (1 USD = 1.72 ANG) which had a fixed exchange rate with the U.S. dollar.

With the CAS islands, it is a different matter. Curaçao and Sint Maarten share a central bank (CBCS) with a domestic currency called the Netherland Antilles Guilder (just mentioned). Curaçao, Sint Maarten, and the BES Islands were part of the Netherland Antilles political unit until 2010 when the Dutch parliament dissolved it for characteristically complicated reasons. Aruba also has its currency, the Aruban Guilder, fixed to USD. Not only did Curaçao and Sint Maarten decide to retain the Netherland Antilles Guilder, but they even planned to replace and transition it to a new currency called the Caribbean Guilder which will again be fixed to the U.S. dollar.

There is no discussion about fixing the exchange rate to the Euro. In this case, all I have said previously applies: a fixed exchange rate is just an unnecessary increase in transaction costs. There is no added benefit beyond having an expensive symbolic trophy. There is no apparent reason why all of the Dutch Caribbean should not substitute their currencies for the dollar.

The British

You will find six of the remaining fourteen British Overseas Territories in the Caribbean. These are not independent countries but unincorporated states of the United Kingdom (though not technically part of the U.K.). While they have elected parliaments, they all have British Governors representing the King of England as the Head of State. This is not a mere ceremonial arrangement. As recently as 2009, the U.K. Parliament dissolved the elected Parliament of the Turk and Caicos Islands following a substantial report detailing rampant political corruption and abuses of power. The U.K. imposed direct rule, with the Governor being granted authority to rule until the underlying issues were reasonably addressed and a new election held.

In 2022, the Governor of the British Virgin Islands commissioned a masterfully nuanced (nearly 1000 pages) report of inquiry, which again recommended the U.K. impose a direct rule on the BVI to address the corruption scandals. (Over then, PM Liz Truss did not agree to impose direct rule in this instance). It is vital to consider all of this when considering the appropriate currency selection choice.

Like most Caribbean countries, BVI is a services-based economy and not physical goods-based. Estimates suggest that over 90% of the BVI economy is services based. The two primary service sectors are tourism and financial services. Tourism in the BVI contributes around 60% of the general economic output and about two-thirds of employment. A report to the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee stated that financial services accounted for 33% of the BVI GDP and 60% of its government revenue (of which this revenue primarily comes from incorporation fees).

In such a service-based economy, the relevant question is what is the currency of choice of the consumers of the services. As the report of inquiry stated, the tourism sector “is particularly sensitive to external factors such as the health of the U.S. economy and natural disasters,” and the financial services sector was “initially driven by interest from the U.S.” Unsurprisingly then, the British Virgin Islands has been officially dollarized since 1959.

Similarly, the Turks and Caicos Islands are also officially dollarized even though it is British overseas territory. Jamaican dollars were used domestically until 1973 when Turks switched to the USD. The other major British overseas territories in the Caribbean (Bermuda and the Cayman Islands) have fixed exchange rates to USD. And yet again, fixed exchange rates merely unnecessarily increase transaction costs. In such cases, there are no apparent reasons not to dollarize.

The French

There is a part of France (an overseas department) located in South America named Guyane/French Guiana. It is around the same size as Austria, one of the original five Guianas divided up in the colonial period.

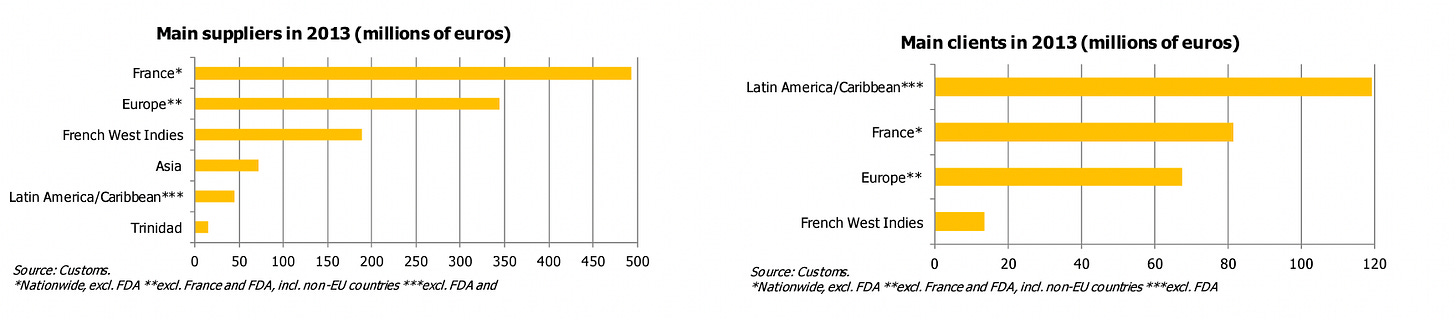

While this jurisdiction is as big as Austria, it has a population of just around 300,000. And though located in South America with a geographical Caribbean orientation, it does very little trade with its region, and most of its trade is with France and Europe.

As with other Caribbean countries, a significant part of the economy is services-based. What is unique (and honestly weird) about Guyane is that the primary services industry is not tourism but space sciences and rocket launches. The Guiana Space Center - Europe’s Spaceport is located in French Guiana. Some estimates suggest that the space center and related jobs account for almost 20% of the GDP of Guyane. Many European researchers, for example, also frequent the country.

With these points in mind adopting the U.S. dollar would not be the most advantageous strategy. But it would also be unwise for Guyane to have its domestic currency given that it still needs to make most of its international purchases with euro-based economies. Prudence would dictate that Guyane should be using the Euro as its sole currency. And that is precisely the case, and Guyane adopted the Euro in 2002.

There are more aspects of the currency substitution discussion that we can assess in the Caribbean that will occur in future posts in this dollarization series.

What would be the actual cost of dollarization?

There is an argument that dollarization would be very expensive, and the one-time startup cost to switch the domestic currency supply to dollars would be significant. But that is not the case. Remember that most of the “money” in a modern economy is digital, not physical. The way you “convert” the digital money of Jamaica would be for the government to coordinate the database adjustment of banks to convert all references to USD at a specified prevailing market exchange rate.

For the physical notes in circulation, the government would set a conversion rate based on prevailing market conditions at a point in time and allow Jamaicans to exchange Jamaican cash notes for USD notes at their respective banks within a specified window of, say, three months.

The USD notes would be simple to acquire. Looking at the balance sheet (above) of the central bank of Jamaica, we see that right now, there is about JMD $226,580,371,000 (Jamaica Dollars) worth of notes in circulation. (Also, yes, Jamaica launched a Central Bank Digital Currency, CBDC — which will be discussed in detail in a future blog in this series). These JMD notes are worth the equivalent of $1,473,274,513 USD at the currency exchange rate. That means the government of Jamaica would need to acquire that amount in physical USD.

Remember that governments of Caribbean countries hold USD reserves (in the form of Treasury bills and securities) at banks in the US. These are practically equivalent to cash. Therefore, Jamaica would simply need to convert a portion of their USD reserves (already held in the US) from Treasury securities to physical cash and then have that cash shipped to Jamaica. Looking again at the balance sheet (above), it is evident that Jamaica has more than enough USD reserves (foreign assets) to perform the conversion. The decrease in USD reserves won’t be a problem as the primary reason for reserves would be to stave off balance of payments crunches - which can now be wholly avoided if USD is solely used for transactions.

The switching costs, as can be seen, are minimal. The government would need to educate the population about the process and allow enough time for the switch to occur fluidly. No one is advocating for a fiasco like in India in 2016.

The next substack entries in this series will cover more details on the dollarization process of Ecuador and El Salvador. I will also dive into more of the common semiotic objections to dollarization.

Please leave your comments or critiques in the comments!

What do you think are the strongest arguments against dollarization?

The linked news article (https://www.batimes.com.ar/news/argentina/mileis-policies-and-poll-numbers-spark-concern-in-argentina.phtml) about the Argentine dollarization proposal quotes a consultancy warning about the following:

> If the market perceives that Milei has any chance of governing, it is most likely that we will see a run against the peso. It could even generate a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy, with peso-holders fearing dollarisation and trying to get rid of their holdings, [thus] creating the conditions for this dollarisation.

What makes this a plausible risk for Argentine dollarization, but not Caribbean dollarization? Or is it a plausible risk for both? Or neither?

By the way, the St. Martin map is probably the only map in existence using 'baie', 'bay', and 'baai' in the names of three adjacent locations.

Just a note: The de facto currency of St. Maarten is the USD. While a few shops on St. Maarten list prices in Netherlands Antilles Guilders, most do not, whereas everywhere in Dutch St. Maarten lists prices in USD. Many businesses will not accept NAf as a form of payment, and the ones that do are still real confused if someone tries to pay in guilders. This is the case even though cash transactions are still very common on St. Maarten.