Noah Smith wrote a series on his substack about the economic trajectory of some developing countries. I genuinely enjoy reading Noah’s work. But his piece ‘Jamaica is doing OK’ is incongruent with the reality of Jamaica. I don’t think the problem is necessarily a lack of information but rather a lack of context.

In this post, I want to do two things. Firstly, I hope to persuade Noah to revise his working theory of Jamaica’s economic performance. Secondly, I want to persuade readers that a context-rich analysis of Caribbean institutional development will aid metaeconomics debates on economic growth and divergence.

Institutions do matter

Noah repeatedly referenced a short paper from Henry and Miller which tried to show that since both Jamaica and Barbados have “virtually identical” institutions their post-independence divergence in economic performance can only be accounted for by difference in macroeconomic policies choices. Essentially, the paper tried to counter the theory that “institutions” (along the lines of Douglass North or Daron Acemoglu) are a significant deciding factor in long-run economic performance.

Before proceeding let’s set out the working definition of “institutions”:

Acemoglu quoting & annotating North

Douglass North (1990, p. 3) offers the following definition: “Institutions are the rules of the game in a society or, more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction.” Three important features of institutions are apparent in this definition: (1) that they are “ humanly devised,” which contrasts with other potential fundamental causes, like geographic factors, which are outside human control; (2) that they are “the rules of the game” setting “constraints” on human behavior; (3) that their major effect will be through incentives.

Now the core argument of Henry and Miller can be described as follows:

Barbados and Jamaica are both parliamentary democracies in the Westminster-Whitehall tradition.

The constitutions of Barbados and Jamaica explicitly protect private property.

Barbados and Jamaica both adopted legal systems based on English common law.

Therefore: “since their initial conditions were similar at the time of independence, it stretches credulity to argue that Barbados and Jamaica diverged because of the difference in colonial origins, legal origins, geography, or some other exogenous feature of their economies.” Further: “We argue that the explanation for the divergence lies not with differences in institutions but differences in macroeconomic policy.”

However, the fallacy of the Henry and Miller argument is in the premise. The initial conditions (pre-independence institutions) of Jamaica and Barbados were not identical. Henry and Miller focus merely on the form but not the substance of the institutions of the two countries.

Additionally, they also sidestepped taking on other institutions such as culture and social norms. If you grew up in the Caribbean you know well that Barbados and Jamaica are similar in many ways but polar opposites in most social tendencies. This should give you pause when thinking they have “virtually identical” institutions. But even if Barbados made different (more prudent) macroeconomic policies than Jamaica would the question not reduce to why were Barbados’ institutions more capable of opening up space for more prudence policies?

I will use work done by Orlando Patterson and Victor Bulmer-Thomas to reaffirm the colonial origins of the institutional divergence between Jamaica and Barbados. Also, I will use this base to suggest why you should be skeptical of claims that Jamaica is doing ok.

Violence is the answer

One litmus test to assess if someone has a robust contextual intuition about Jamaica is to ask what they think about Reggae. If they respond solely with something along the lines of “peace, love, togetherness and solidarity” then they simply have the wrong context. That will only lead to the wrong intuitions. If you truly understand Reggae you know that the core themes cluster closer to “political struggle, rebellion, violence”.

You would know that there was an assassination attempt on Bob Marley. Or that one of his original band members, Peter Tosh, was actually assassinated. Or that another innovator on the Reggae/Dancehall scene, King Tubby, was brutally murdered. Or even that one of the current kings of Reggae, Vybz Kartel, was sentenced to life in prison for murder yet releases #1 Hits from behind bars. There is a bare-metal vulgarity underlying Caribbean culture in general (which I definitely appreciate too) but it is clearly evident in Jamaican culture.

Rastafari are often portrayed as mellow potheads. But even a key founder of the Rastafari movement, Leonard Howell, was jailed several times for sedition. The government often ordered police to raid his ‘church’ to stop him from preaching to his growing congregation. Later the government of Jamaica forced him into a mental asylum where he later died after a brutal attack.

The invention of Reggae in Jamaica was not accidental. In my view, Reggae could not have been invented anywhere else but in Jamaica. It is an outgrowth of the unique cultural institutions of the island stemming from unique socio-historical development.

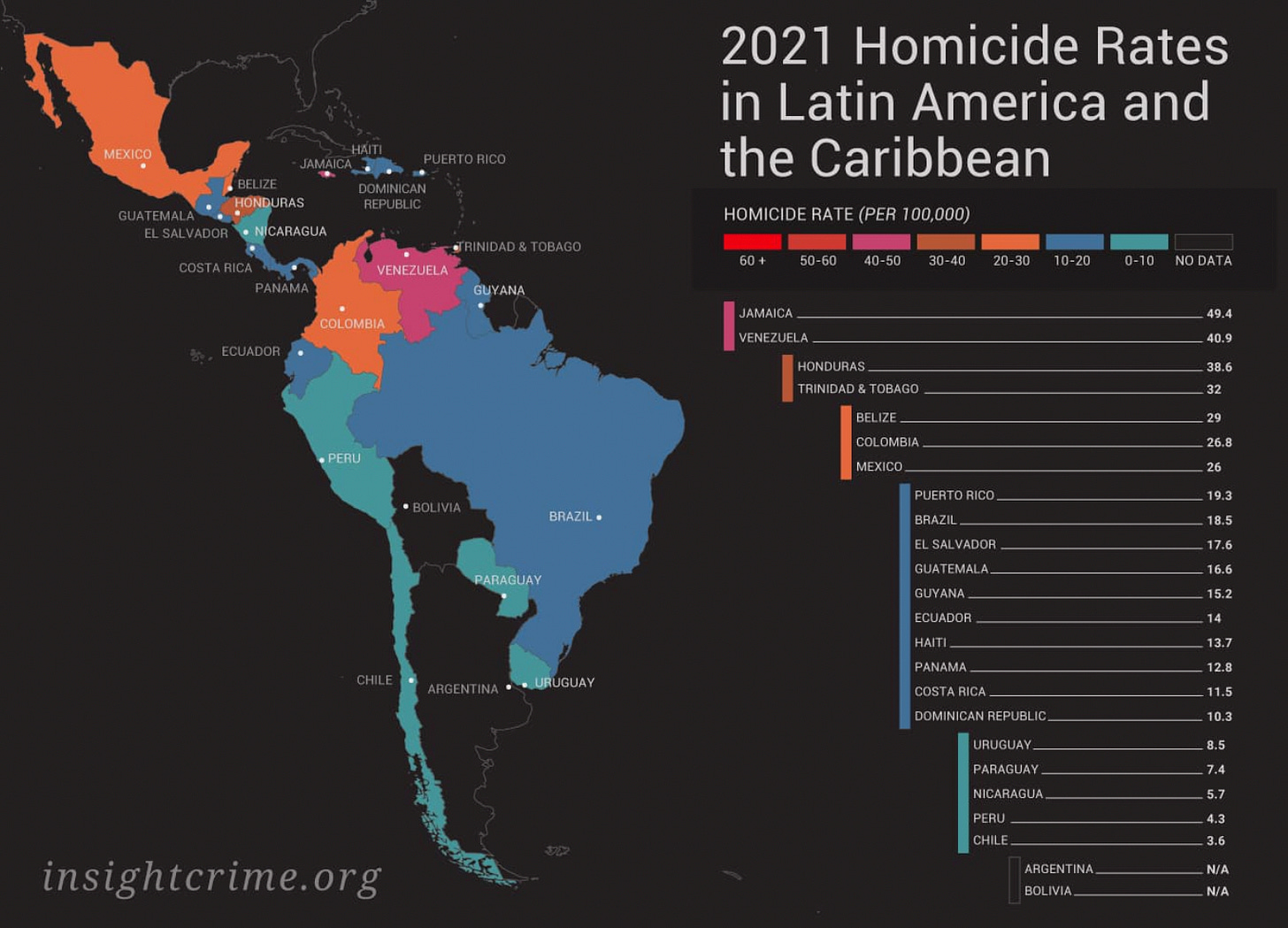

Rabid violence continues to force Jamaica into a convulsion. As recently as December 2022 the Prime Minister of Jamaica declared a state of emergency because of the perpetual killings. According to several indices, Jamaica captures the haunting accolade of the highest homicide rate in the world.

Violence has deep roots in Jamaica. This has significant implications for thinking about Jamaica’s socio-economic institutions today. Every secondary school student who studied Caribbean History knows of the Maroons. (Nanny of the Maroons is a national hero in Jamaica and is also featured on their $500 note). Jamaica’s mountainous and rugged terrain provided refuge, especially during the years of plantation slavery. Many of the enslaved people escaped from the plantations and formed villages in the mountains. From there they constantly barraged the plantations with brutal guerrilla warfare. According to Patterson, this continued for almost the first 70 years of the slave system in Jamaica until the British colonial government signed a treaty with the Maroons to allow for a separate state within Jamaica where the formerly enslaved people would live relatively unencumbered by the British. This was a highly unusual state of affairs and had not occurred anywhere else in the British Empire. Jamaica was unique.

The plantation owners and the British elite in general bracketed Jamaica as an exceptionally dangerous place with a reputation for constant slave rebellions. It is therefore not surprising that the British elite did not have any urge to stay in the country long-term. For those familiar with Jane Austen novels you would recall that in Mansfield Park Sir. Thomas left England to visit his plantation in Antigua (in the Caribbean) because it was being mismanaged and he wanted to set the affairs in order himself. This is a prime example of absentee ownership, which was also prevalent in Jamaica.

Whereas in Barbados, there was a single slave revolt during the entire period of slavery. Barbados was much adored by the British Elite who stayed on the island long-term. A curious history that is little known in the US is that the original settlers of the original colony of Carolina came from Barbados. The usual impression is that they came directly from England but no. There is a great museum in Charleston, South Carolina that details the states origins in Barbados. This is why the plantation system there was much more like Barbados. Several of the main Carolina plantation owners also owned properties in Barbados.

One Empire, Two Systems

Moreover, the slave population of Jamaica never became self-sustaining. The extra brutality of the plantations in Jamaica is thought to be based on the fact that the plantation owners were constantly absent and the persons put to manage the estate on short-term contracts were much more vicious to the slaves compared. Consequently, the slave compliment needed to be replenished more often. Shockingly, data suggests that more slaves were brought to Jamaica than the entirety of the rest of North America.

So then, the culture that formed in colonial Jamaica was constantly infused with new African affinities situated in a hyper-brutal environment with an elite class that was almost wholly absent.

However, in Barbados, the locally-born slave population (“creoles”) exceeded the African-born population a few decades after the slave system was started. Indeed the only other place in the British Empire where this occurred was the US South. This drastic demographic difference with Jamaica would likely have a long-lasting institutional effect. The transition from colony to independent country failed to hit the “refresh” button.

Jamaica experienced no economic growth in exports per capita from the Napoleonic Wars to the end of the Second World Wars. Since there is a high correlation between exports per capita and GDP per capita, at least after 1850, Bulmer-Thomas argues that there are solid grounds for concluding that the Jamaican economy on a per capita basis experienced no growth at all for more than a century after the end of slavery.

After the abolition of slavery in 1834 conditions in Jamaica remained dismal. At this point, sugar exports were still the main revenue earner for the island. But the former slaves refused to work on the plantations so production faltered. This worsened when the British Empire effectively ended imperial preference for exports to England. That is, sugar from slave plantations in Brazil or Cuba, or sugar from India or Mauritius was imported without extra duties. Whereas previously imports from the British colonies into England had a tax advantage over imported goods from other non-British realms. Jamaican sugar became uncompetitive. Yet as the Jamaican economy continued to decay the owners of the sugar plantations refused to invest money to diversify and modernize their estates. There was an institutional void.

After further decades of poor policy management by the Jamaican Assembly (British Elites in Jamaica), the British parliament in England terminated the Assembly and placed Jamaica under direct Crown Colony rule in 1866. All of the other Caribbean possessions of the Crown were also placed under direct rule except one.

Barbados was the only colony which was allowed to have its local Assembly continue because of the active and prudent progress that was occurring to modernize the state and population (what V.S. Naipaul referred to as the movement towards a “universal civilization”). Indeed the Barbados Assembly remained in place up until the 1950s where it transitioned to a self-ruling parliament. That’s over 300 years of locally instituted legislative continuity. When the transition to independence came, the local leaders were already trained and brought into the fold of the third oldest parliament in the Americas (behind Virginia - one of the original 13 colonies in the USA, and Bermuda - still a territory of the UK).

Moreover, by the middle of the 19th century, the black population of Barbados was the most literate in the Caribbean. By the late 19th century, the British authorities decided that Barbadians should be trained and employed in imperial expansion and management throughout the Americas and Africa. This persisted. In 1946 Barbados was 91% literate while Jamaica was 74% literate. There was only an 8-point difference between blacks and whites in Barbados, compared to a 25-point difference between blacks and whites in Jamaica.

Jamaica’s economic performance has been poor for centuries. Noah in his piece mentions that Jamaica’s GDP per capita has not materially grown since 1990. It is far worse than that.

Data compiled by Bulmer-Thomas shows that Jamaica’s GDP per capita is actually around the same level it was at independence.

When you take the long view there is cause for skepticism that that Jamaica and Barbados developed “virtually identical” institutions. Therefore the post-independence divergence was not a divergence at all. A better assessment would be that the immediate post-independence economic boom in Jamaica was a temporary aberration in the top line data.

Conclusion - Voting with your feet

A good way to determine if a country is doing ok is the net migration rate. Every year since 1952 net migration has been outwards from Jamaica. With a population of around 2.8 million in 2021 living in Jamaica, some estimates suggests an equal number are living outside the country. In 1975 Jamaica’s population reached around 2 million. This was roughly the same as Singapore in the same year. But in 2021 the population of Singapore grew to around 5.4 million.

Jamaicans are unambiguously voting with their feet to say that the country is not ok. The country ranks #2 on the Human Flight and Brain Drain Index. Given that #1 is Samoa I can claim that there is no other country on earth with as much brain drain as Jamaica.

The government has shown little to no capacity to implement credible policies to boost employment, lower crime, and propel growth. This is why I was puzzled when Noah wrote this:

And there’s one big reason to be optimistic about Jamaica: The enduring strength of its institutions. In an age of advancing autocracy, Jamaica remains resolutely democratic, scoring higher than the U.S. on some international measures. It’s an island (heh) of political stability in the region.

The political establishment is so corrupt that there is a term specifically applied to it: garrison politics. “A garrison is an area in which criminal and political activity are tightly controlled by politically affiliated gang leaders.” Paul Romer saw the situation as so dire that he even argued that the only way to inculcate the correct political incentive in Jamaica towards implementing good policies would be to allow absentee voting of Jamaicans living outside the country. As it stands only those persons living inside Jamaica can vote in elections.

“Jamaica never gets worse or better, it just finds new ways to stay the same.”

― Marlon James, A Brief History of Seven Killings

Jamaica has given so much to the world. But its institutions never evolved to properly deliver sustained economic growth to its citizens. It is not sufficient look at uncontested election cycles to praise the “enduring strength of its institutions.” We should maintain higher expectations of Caribbean governments and not sidestep the underlying impediments to progress.

I learned a lot from this post.

> If you grew up in the Caribbean you know well that Barbados and Jamaica are similar in many ways but polar opposites in most social tendencies.

In your first post, you shared a reading list. Would you recommend one of those books in particular as the best place to go to for a variety of comparisons and contrasts like this? For example, I would like to read a book that spends a few pages comparing Haiti, Guadeloupe, Martinique, and French Guiana; a few pages on Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico; a few pages on Haiti and the Dominican Republic; and a few pages on Belize, Trinidad and Tobago, and Jamaica.

This was an excellent post. I really enjoyed reading it and look forward to your next one.