How Anguilla Profits from the AI Race

Anguilla and other micro-states are striking it rich via domain sales

You might not have heard of Anguilla, a Caribbean island that lies east of the Virgin Islands. One of Britain’s 14 overseas territories, Anguilla has a population of 15,780 (just over 3000 in its capital - The Valley) and is about 2.9 times the size of Manhattan. To the Internet Domain Name System, however, the tiny tropical island of Anguilla isn’t much different from India or Canada. It too, is entitled to a domain extension: .ai.

The AI boom created a new interest in Anguilla’s country code top-level domain, or ccTLD, as tech companies like Character.ai, Perplexity.ai, and Elon Musk’s X.ai opted for the less conventional suffix. Since the release of ChatGPT in November 2022, the total number of .ai domains has doubled. It amounted to a total of 287,432 by late August, according to Vince Cate, the technical manager for .ai.

Domain sales are generating revenue for Anguilla’s government. Per Cate’s estimate, the domain registry is currently generating $3 million in revenue every month for the government, which is somewhere around a third of its monthly budget.

Anguilla isn’t the only micro-state with significant government revenue from domain sales, though its relative scale is unmatched. Tuvalu, an island nation in the South Pacific, famously paid for its entry to the United Nations by selling the license for .tv to a US firm at the height of the dot-com bubble; its government made close to $5 million from ccTLD sales in 2022, or 8% of its total revenue that year. Montenegro’s revenue from the .me domain amounted to 2% of total exports in 2015, with the vast majority of the registrant coming from abroad.

These top-level domains are sold, traded, and auctioned as commodities—to be exported by small governments to foreign startups, registrars, and investors in exchange for revenue. But it hasn’t always been that way: in fact, the internet’s early pioneers had intended these digital resources to be community-run infrastructure that served a public function.

The story of domain names begins with the ARPANET. Commissioned in 1968 by the US Department of Defense for research purposes, the Internet’s precursor was reaching universities across the United States. Machines were able to communicate with each other—exchanging data and transferring files—through socket numbers. While it was customary to use specific socket numbers for certain tasks, users who weren’t aware of these common practices could potentially create confusion, if not chaos. In 1972, a computer scientist at UCLA named Jon Postel half-jokingly appointed himself as the “czar of socket numbers”—a central authority who allocated identifiers to users on the network.

It’s easy to be a czar in a small town like the early ARPANET, where everybody knew everybody; its expansion and transition to the internet in the 1980s, however, saw two changes. First, because socket numbers (and later IP addresses) are hard to remember, the Domain Name System (DNS) was implemented to allow for access to computers by their unique text-based domain names. Second, Postel’s one-man team could no longer allocate domain names for everyone on the internet. He proposed generic top-level domains (gTLDs) like .com, .org, .gov, and .mil to be managed by their respective registrars, which oversaw all registrations under its extension. The internet becoming public also meant that it was global, so Postel and his colleague Joyce Reynolds envisioned a domain suffix for each country—a scheme that would later become known as ccTLDs.

The first ccTLD in use was .us, originally created in 1985 and administered by Postel himself. But for other countries, he appointed local managers. The establishment of ccTLDs often predated government internet authorities, so the administrators were often university labs or computer researchers. His delegation was on a first-come, first-served basis; he suggested in ARPA’s MsgGroup that the “responsible person” for second-level domains “is generally the first person that asks for the job.”

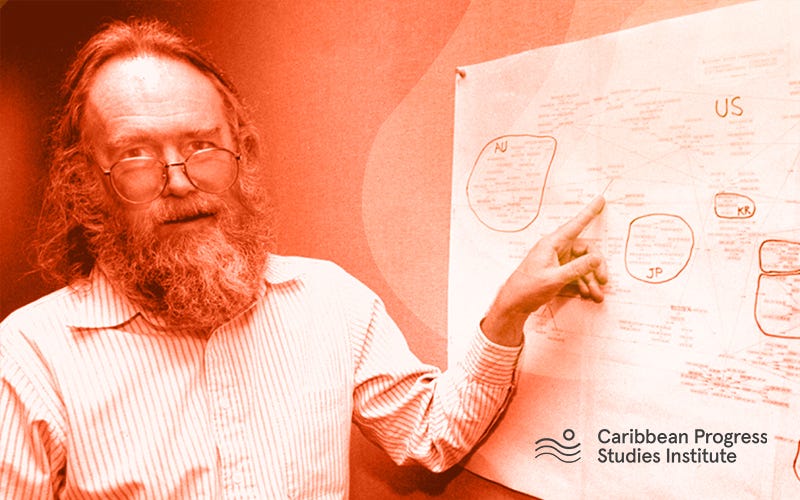

In 1994, the California native and Berkeley libertarian Vince Cate dropped out from his PhD program at Carnegie Mellon, where he was designing the Alex filesystem. He wanted to relocate to a tax haven but couldn’t afford living in Bermuda or the Cayman Islands. He moved instead to Anguilla, where he paid $470 a month on rent to kickstart an email business. In Anguilla, he was the first to email Postel, who told him that there wasn’t anyone managing Anguilla’s TLD yet and suggested he be the first volunteer manager of .ai.

To Postel, who passed away in 1998, domain names were nothing but identifiers; they had no economic value. Due to the low number of registrations, domains were free of charge until 1995. For years, Vince Cate gave away domain names to any Anguillan business that asked for one. In a bygone era when the web was much smaller, Postel’s vision for allocating digital resources was unabashedly communitarian. “Concerns about ‘rights’ and ‘ownership’ of domains are inappropriate. It is appropriate to be concerned about ‘responsibilities’ and ‘service’ to the community,” he wrote in 1994, after his volunteer role had been formalized into the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA).

During the dot-com boom, however, the internet was becoming a hotbed for attention-thirsty startups and get-rich-quick schemes alike—the rosy picture of a closely-knitted community began to seem naïve. For one, ccTLDs in countries with a growing number of internet users took many volunteers to operate. Domain names were used for spam mail, online scams, and other illegal activities. Cyber-squatting—the practice of registering trademarked domain names—became tricky to regulate. Meanwhile, web addresses were increasingly recognized as valuable digital assets as domain resellers sold premium names at high prices. These circumstances soon rendered Postel’s first-come, first-served principle of ccTLD delegation unsustainable.

In the early 2000s, the IANA was swamped with requests for re-delegation. Seeing ccTLDs as a public good, some states established government bureaus to take things into their own hands; others, like Canada, incorporated not-for-profit organizations in collaboration with the private sector and academic institutions. Many registries, such as .us and .fr, introduced regulations to limit domain registrations to individuals or organizations with actual ties to the country, though they’re enforced to varying degrees. This process of formalization—the transfer of administrative power from volunteers to governments—was complete in most major countries by the early 2000s. In Anguilla, too, Cate changed the administrative contact of .ai to the government of Anguilla, which gladly kept him as the technical manager.

But this wasn’t the case everywhere. The internet reached the world’s periphery later than its core, and some nations weren’t even aware that they were entitled to a piece of the global namespace when their domain name had been assigned to, well, randos. Before Tuvalu sold its .tv license to Verisign, the extension was managed by a programmer in the United States with no relation whatsoever to Tuvalu. Another American was given the control of .nu, reserved for the South Pacific nation of Niue.

Some, like Niue, were never able to retrieve control from foreign firms that profited off their digital assets. The island, which wrote into law that .nu was a “[n]ational resource for which the prime authority is the Government of Niue,” sued the Swedish firm that now owned the rights to its ccTLD in 2018. The claim is still being contested, and neither the Niuean government nor its people has received any profit from the domain sales, which is estimated at somewhere between $27 million and $37 million since 2013.

Others, lacking the capacity for an in-house domain sales operation, outsourced root server management and marketing to third-party registries, often based in the United States or Europe. Tuvalu’s .tv domain is currently managed by GoDaddy, which pays a portion of the sales revenue every year to the island’s government. Countries like Tuvalu “are often getting a very bad deal,” Vince Cate said.

Consider the familiar .io, popular in the developer community (and later the cryptocurrency industry) as a shorthand for “input/output.” It was assigned to the British Indian Ocean Territory which sits on the colonized Chagos Islands. In 1968, the British forcibly expelled the native Chagossians to construct a military base. Jon Postel had delegated the rights to the suffix in 1997 to the Internet Computer Bureau (ICB)—a UK company with only a care-of (c/o) address in the territory. Refugee groups have filed a lawsuit against the .io registry, whose domain sales profits never reached the Chagossians—nor the British government, which repeatedly denied having received any payments.

The illegitimate squatting of ccTLDs has become a clear case of digital colonialism: the exploitation of digital resources by Western capital came alongside the commodification of ccTLDs. But domain names aren’t tangible like tea leaves, labor, or land; just to what extent does their sovereignty matter?

The 20th century witnessed the globalization of technology and communications: postal services and banking, for instance, needed a unified coding system to make sure that parcels and wire transfers were going to the right country. In 1974, the International Organization for Standardization published its first country-code standard. ISO 3166-1, which included an alphabetical abbreviation for each country, would serve as the basis for future inventions like top-level domain naming and machine-readable passports.

Whether a country can be viewed as deserving its own ISO code, however, doesn’t always have a straightforward answer. The ISO didn’t want to take a stance on territorial disputes, so it borrowed the list from the United Nations, though for practical purposes, some territories and dependencies were given their own assigned codes. (Taiwan gets its own code as a “province of China.”)

But this meant that unrecognized sovereignties in the United Nations don’t get recognition in the digital space, either. Kosovo, which Serbia claims to be part of its territory, doesn’t have its own ISO country code because it is not a member of the United Nations. Not having its own ccTLD made it difficult for residents to search for localized information and businesses to target local audiences. Similarly, the de facto independent Somaliland was never assigned a ccTLD; its government banned the use of .so domain names after the Somali government, which claims Somaliland, nationalized its registry in 2018.

The entitlement to codification is, therefore, a political act—it establishes, negotiates, and rejects claims to autonomy and sovereignty of individuals and communities. “For any individual group or situation, classifications and standards give advantage or they give suffering,” wrote Geoffrey C. Bowker and Susan Leigh Star in their seminal work Sorting Things Out.

The life and death of domain suffixes are products of revolutions, warfare, diplomacy, and displacement. They are born out of new regimes and die of political dissolutions. Former Yugoslavia’s ccTLD, .yu, was previously used by its successor government Serbia and Montenegro until the union’s breakup in 2006. Montenegro’s very popular domain, .me, was made possible, while Serbia was left with .rs. The Yugoslavian extension officially retired in 2010; all existing domains were phased out.

Anguilla’s road to becoming the .ai clearinghouse itself was the product of a complex set of geopolitical intrigues—for one, it didn’t start with the “AI” country code. The original ISO 3166-1 scheme in 1974 assigned “AI” to the French Territory of the Afars and the Issas, a short-lived colonial regime after the failed independence of French Somaliland; Anguilla, then under the British colony Saint Kitts–Nevis–Anguilla, was allocated “KN.” But this arrangement didn’t last long. The Afars and Issas voted for independence from the French empire in 1977 to form Djibouti; subsequently, “AI” was to be replaced with “DJ” to symbolize the birth of the new African republic. After a secessionist movement against Saint Kitts and Nevis that lasted for more than a decade, Anguilla became its own British dependency in 1980—while its neighbors became its own sovereign state in 1983. With the Union Jack back on, the ISO reassigned the two-letter code “AI” to the island.

The economy of domain names is as fragile as territories. Tuvalu is under existential threat from rising sea levels: the country might become uninhabitable by the end of the century. It’s possible that the British Indian Ocean Territory won’t exist one day—international courts have ruled against British occupation of the Chagos Islands, and the UN General Assembly called for the archipelago’s decolonization in 2019. If these names are struck off the ISO list of countries, we might be left with a world of dead links. The loss of domain names will be trivial compared to the real-world implications of lost lands and lives, yet the cultural heritage that comes with it will, too, be consequential.

In more recent times, digital standardizations from domain names to national flag emojis—which also follow ISO 3166-1—have been used to signal sovereignty and resistance. Some Quebec nationalists are using Martinique’s 🇲🇶 drapeau aux serpents—which is no longer an official banner for the French overseas region—as a fleur-de-lis lookalike. After Catalan nationalists had preferred non-Spanish domains—such as Gibraltar’s .gi for Girona—until the sponsored TLD .cat, proposed by the Catalan non-profit puntCAT, was approved by ICANN in 2005. But ahead of Catalonia’s proposed independence referendum in 2017, the Spanish government raided puntCAT and arrested its executives.

Almost three decades later, Vince Cate is still operating the .ai registry largely by himself, occasionally with help from a few others. He gets paid for running the registry, but most of the revenue goes to Anguilla’s government. “It’s hard to find somebody else that has more than 20 years of experience single-handedly running a TLD,” said Cate.

We’ve yet to see what Anguilla’s government will do with its newfound source of wealth. Government monopolies are easier to justify when it comes to public goods, but when domain names are commodities, it’s worth asking who benefits from these exports. Meanwhile, this income might not sustain: this current AI fad will ebb, and even if it doesn’t, .ai won’t always be a powerful brand signal—just like TikTok isn’t using .tv.

With the current rate of growth, though, “it’s completely conceivable that we could get to where we don't need local taxes—or at least they could get rid of taxes on food or groceries,” Cate told me from his home in Anguilla. “As a libertarian, I would love to see that.”

Tianyu Fang is a fellow at the CPSI. Follow him on Twitter and Substack.

This article was originally published on Reboot.

Make sure you don’t miss out on our Deep Dive pieces on the Caribbean 👇