Dollarzone Banking in Panama: Intellectual Origins

Notes Towards Caribbean Dollarization (Part 3 of 17)

Significant attention has been paid to Chile's development using free-market principles via “Los Chicago Boys.” In this piece, I want to highlight that Panama’s large, financially integrated dollarized international banking center (and, therefore, a significant part of its economic growth) also traces its origins to the free-market principles and guidance of another “Chicago Boy” who became Panama's president.

This post is Part 3 of a planned multi-part series explaining the benefits of Caribbean Dollarization and dissolving the relevant counterarguments. These public notes aim to compile the best arguments for a larger project. In Part 2, I explained the curious historical circumstances of how Panama dollarized in 1904. As always, comments are open.

Panama's dollarization is often said to be the basis for its high degree of financial integration. While this is true, I have never found any research answering why a small country in Central America became so financially integrated in the first place—or rather, why Panama developed a banking sector that is significantly autonomous from state control. I will explain why this result can be traced back to Nicolás Barletta, who had a short tenure as President but whose entire career shaped Panama's financial policies and intellectual foundations of economics management.

But first, some context.

Dollarzone Banking

Panama has around 4.5 million people and a GDP of $76 Billion.

In the early 1960s, Panama had just four small banks. Today, in 2024, according to the Superintendencia de Bancos de Panama (SBP), which regulates the banking sector, there are 64 registered banks. In comparison, Colombia, with a population of over 51 million, has just around 20 banks. Costa Rica has a population (of 5M) similar to Panama, but with 17 banks.

The banking sector represents around 7.3% of Panama's GDP and employs over 25,000 people directly. Total banking deposits relative to GDP for Panama are about 138%, which is substantially higher than any other country in the region (and higher than most countries globally). If you take Colombia, banking deposits are about 45% of GDP; El Salvador 35% (also dollarized); Chile is around 75%, etc.

Unlike other regional countries, Panama’s banking sector largely comprises international banks that primarily (or solely) offer services to non-Panamanian customers. Banks based in non-dollarized countries can open subsidiaries in Panama to do business back home. Panama’s regulations and completely open capital flows enable this. I’ll give a concrete example.

Banco Popular (Dominicano) is the largest bank in the Dominican Republic. It is part of the holding company Grupo Popular S.A. It is a standard commercial bank that offers both customer and institutional products. If Dominicans go to their local bank’s website, they can get a range of credit cards, mostly in Dominican Pesos (RD$, the national currency), but also a few options denominated in USD.

For example, the screenshot above shows the “Gold International” credit card billed in dollars: “No matter how far you travel, use your card at affiliated establishments, and your consumption will be billed in dollars.” This is attractive to consumers in the Dominican Republic because they mostly travel to the USA and prefer to have everything accounted for in dollars. But remember that the Dominican Republic itself uses only DR Pesos, not dollars.

To circumvent this, Banco Popular issues USD credit cards from a related Panamanian entity called Popular Bank Ltd. This is explicit in the Terms and Conditions on the Dominican website.

Like Banco Popular, Popular Bank Ltd., the Panama entity, is 100% owned by Grupo Popular S.A, located in the Dominican Republic. Dominicans assume they are simply getting a card from their local bank branch, but instead, it is issued internationally from Panama.

Panama is a dollarzone market with a regulatory environment that does not discriminate between domestic and international customers. Along with a Hispanophone workforce, it has become a banking center for Latin American countries. For other countries that are not dollarized (like the Dominican Republic), banks can still offer their domestic clients access to dollars by operating from Panama.

Many loans for large construction projects in Latin American countries are sourced from banks in Panama because they can be made in dollars rather than the volatile domestic currency. In this sense, Panama’s dollarzone international banking helps to de-risk credit portfolios across Latin America. This feature is not usually discussed. One expert informed me that the Bank of China, for example, ranks Panama as a Tier 1 liquidity center on par with New York for its global credit operations.

There is much more to explain about Panama’s banking center operations, but I want to discuss its origins in this piece. The first substantial law (Decreto 238) to kick off the current banking sector was relatively recent, enacted in 1970. This is a strange year to have a law passed with a high degree of free market principles. Why? Because in 1970, Panama was still under a military dictatorship led by Omar Torrijos.

What Torrijos Did

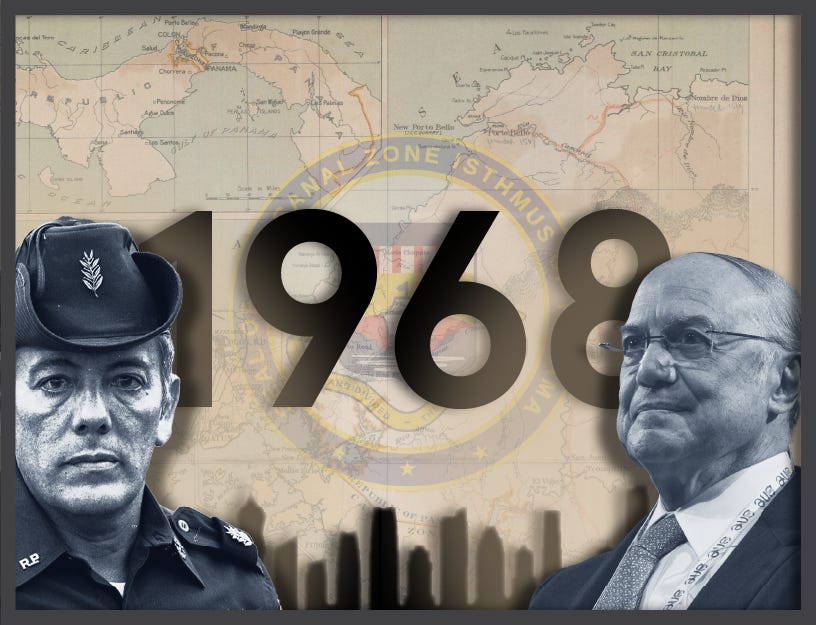

In Part 2, I discussed President Arnulfo Arias Madrid, who was removed from office by a coup d'état in 1941, seven days after he tried to create a new paper currency in Panama. President Arias was elected back in 1951 and was again removed by a coup. Yet again, President Arias was elected in 1968. And yet again, he was removed by a coup on October 11, 1968, just after ten days in office. This coup was led by Lieutenant Colonel Omar Torrijos of the Panamanian National Guard. Torrijos was about 40 years old at the time.

Ironically, President Arias fired Colonel Bolivar Vallarino, the head of the National Guard, soon after he came to office to prevent another coup from taking him out. Still, this action ultimately provoked Torrijos to lead a new coup against Arias.

Torrijos led the military government (and was, therefore, the de facto leader) of Panama from 1968 until he died in a helicopter crash in 1981.

Omar Torrijos’ was laid to rest in an extravagant tomb in Panama that still receives ceremonial visits on some holidays. His son, Martin Torrijos, was democratically elected President of Panama from 2004 to 2009.

Omar Torrijos is a complicated political figure. While he was technically a military dictator, he was also unequivocally the most influential leader regarding positive economic growth.

Torrijos was the person who got the USA to give control of the Panama Canal (and the Canal Zone) over to the Panamanian government. This was confirmed in the Torrijos–Carter Treaties 1977, signed between him and President Jimmy Carter. It is not common knowledge now, but back in the 1970s, the transfer of the Canal was one of the most heated political topics in the USA.

In 1978, when Congress was about to ratify the Torrijos-Carter Treaties, there was a debate, which can be found on the C-SPAN website, between Ronald Reagan and William F. Buckley, where Reagan was in strident opposition to the handing over the Canal:

“We cannot abdicate our responsibility for the operation of the canal and the security of the western hemisphere. Let us reject these treaties…” — Ronald Reagan

Without the Carter administration, the Canal would unlikely be under Panamanian control today. Reagan was elected President the year after he gave that speech and would not have been persuaded otherwise.

But what Torrijos was able to achieve is undoubtedly miraculous. The United States funded, designed, built, and managed the most critical mega-project of the century and then just gave it away to a small country. The details of this are fascinating but outside the scope of this post—I’ll get into that topic in the future.

Revenue from the Canal and its related services are now a key pillar of the economy. Panama has Latin America's highest GDP per capita (PPP), at $32,768. Between 1990 and 2019, the annual average GDP growth was around 5.9%. However, the canal was not the only economic pillar. The liberal banking sector, which accounts for around 7% of GDP, also stems from Omar Torrijos' dictatorship.

When Torrijos took over the government, one of his main economics advisors was Nicolás Ardito Barletta Vallarino, who was around 30 at the time. Barletta returned to Panama after completing his PhD studies in Economics at the University of Chicago and joined the government of Torrijos the very next day after the coup was complete. Barletta was one of the main negotiators in the Torrijos-Carter treaties for the Panamanian side. A glimpse into his ideological framing can be seen when, later in life, he was asked what he considered to be one of his greatest achievements in those negotiations; he said:

“The creation of an autonomous Panamanian institution [to manage the canal], with a board that is renewed little by little so that it is not controlled by any politician…”

Indeed, to this day, the Autoridad del Canal de Panamá remains autonomous and technocratically managed—a feat so astounding for a Latin American country that some scholars point to this entity as an example of the puzzle of Panamanian exceptionalism. From the coup until the new constitution of 1972, legal rule in Panama was by decree. So, the Banking Law of 1970 was the direct brainchild of its designer because it need not be watered down by a deliberative process.

Nicalás Barletta oversaw the implementation and management of the law that he designed. So, it is necessary to know Barletta’s economic principles to understand why Panama’s banking sector was formed uniquely. I will come to this shortly. We need to take a slight divergence to Chile for some needed context.

“Los Chicago Boys”

Augusto Pinochet in Chile is the most well-known Latin American military dictator who implemented free-market reforms. However, the fact that Latin America had more than one military dictator who implemented significant free-market economic reforms is a very under-discussed theme.

The best book on this topic, as recommended by Tyler Cowen, is The Chile Project: The Story of the Chicago Boys and the Downfall of Neoliberalism by Sebastian Edwards. In 1973, General Pinochet led a military coup against President Salvador Allende and his government, who were self-declared socialists.

When Pinochet consolidated his new military government’s political power, he adopted a set of economic reforms and policies designed by a group of Chilean Economists who studied at the University of Chicago. It is commonly but erroneously said that Chicago economists like Milton Friedman guided the Pinochet government directly. The actual story is more interesting. Indeed, there is a full-length documentary on this topic.

In the 1950s, a small group of graduate students from the Catholic University and the University of Chile were funded to study in the economics department of the University of Chicago. The aim was to upskill several Chileans to teach rigorous economics at those universities in Chile. At Chicago, they studied under the supervision of the leading economics scholars of the day who taught at the school. This, of course, included Friedman but also persons like Arnold Harberger (who will be 100 years old this year) and Lary Sjaastad.

The documentary clarifies that Harberger, who speaks fluent Spanish, was the key influence on the young Chileans. The Chilean students even introduced Harberger to the (Chilean) woman who eventually became his wife in 1958 until she died in 2011.

After studying in Chicago, they returned to their university in Chile to teach the style of economics they had learned. However, their teaching method was notoriously difficult for the students at the Chilean University, and the other faculty members called them “Los Chicago Boys.”

In 1969, the Chicago Boys decided to write an economic program to present to one of the candidates for the upcoming presidential election: Jorge Alessandri. Alessandri was the President of Chile from 1958 to 1964. He was from a political dynasty, and his father was also a former President of Chile. He was anti-Communist/anti-Socialist, and the Chicago Boys supported him.

They wanted to put their free market principles to work and design what they thought would enable rapid economic development in Chile, which Alessandri could use in his campaign and his administration if he won. The completed economic proposals from the Chicago Boys are known as “El Ladrillo” (the brick) because the stack of paper they were typed on was very thick and heavy (like a brick). You can read the original proposals here (in Spanish). Alessandri did not accept the proposals, but it seemed that it would not matter because he lost the election in 1970 to Allende.

Three years later, when Pinochet completed the coup and took control of the government, he decided to implement El Ladrillo and install many Chicago Boys into positions of power. Their economics program was not written directly for Pinochet; it just happened that after he read it, Pinochet thought it was the correct program to implement.

Sergio de Castro, a Chicago Boy in the above picture, became the Minister of Finance under Pinochet and led the economic program. And the “Chilean Miracle” began. It was the first wide-scale implementation of classical liberal principles by any country. In The Ascent of Money, Niall Fergusson identified Chile’s technocratic free market reforms as “far more radical than anything that has been attempted in the United States, the heartland of free market economics… Thatcher and Reagan came later.”

It went exceptionally well until recently when many free-market reformers retired or lost their seats in the erroneous favor of more left-wing government figures.

Barletta — The Other Chicago Boy

Let’s return to Panama. Nicolás Barletta completed his PhD in Economics at the University of Chicago in 1971.

I wondered if he had the same advisors and/or influences as the Chilean “Chicago Boys” while studying. But there is no information about this online. So I figured that if he did a PhD, then in his dissertation, he would mention his supervisors by name. PhD supervisors tend to have a significant influence on a student’s thinking and ideological development.

And that is precisely what I found. In Barletta’s dissertation, he wrote:

“In preparation of this study, acknowledgment is due in the first instance to Professor T.W. Schultz for having introduced me to the subject and to the importance of it in a context of economic development…”

“My deep appreciation goes also to Professors A.C. Harberger, Zvi Grilliches, D.G Johnson, and L.A. Sjaastad for their cooperation and guidance at several stages of the study.”

Barletta explicitly mentions Arnold Harberger and Larry Sjaastad, both key influences on the Chicago Boys in Chile, as discussed previously.

(Thanks to Matt Teichman for digging through the library at the University of Chicago to get me a physical copy of Barletta’s Ph.D dissertation from 1971.)

It could be argued that Panama’s banking sector can also be framed as a success story for Chicago Principles, similar to Chile. I’ll also mention that Barletta was also one of the principal negotiators in the Panama Canal handover treaties and was instrumental in setting up the frameworks to manage the canal.

In an interview with Radio Panamá, Barletta noted that when he returned to Panama after studying for his PhD at Chicago, he realized that the “system had an innate fragility” because it was governed by the laws set out by President Arias in his first administration. These laws were not conducive to the growth of banking liquidity and would constrain the economy.

He recommended that the country emulate others like Luxembourg and “take advantage of the eurodollar market to create a banking center in Panama” [my translation]. This key insight led Panama to its current status as an international banking center. I’ll explain why.

These days, the term “eurodollars” is a bit confusing because people usually think it refers to Euros (EUR), the monetary unit of the European Monetary Union. But it predates the EMU by decades. Eurodollars initially referred to USD-denominated loans and deposits originating in Europe. Over time, the term expanded to encompass any USD-denominated banking deposits outside the U.S. More recently, instead of eurodollar, you will sometimes see it referred to as “offshore dollars.”

The precise origins of eurodollars are debated, but it is generally agreed that the practice started around the late 1950s without the knowledge of the U.S. Federal Reserve or Treasury. The market for eurodollars significantly expanded in the mid-to-late 1960s because of increased US domestic regulation, which made U.S. banks seek alternative means to make foreign loans.

Starting in 1963, the U.S. government under President Kennedy and then under President Johnson attempted to curb what they thought was a deteriorating Balance of Payments position by tightening the controls on U.S. banks under the Voluntary Foreign Credit Restraint Program (VFCR). The VFCR intended to limit U.S. banks' and financial institutions' foreign lending and investment activities. Over the next few years, the controls became tighter, and the U.S. responded by creating more branches outside the U.S. to avoid compliance with the stringent domestic regulations that limited their global ambitions.

In effect, programs like VFCR led U.S. banks to rapidly globalize to meet the international demand for their services and USD-denominated products. This led to a market-driven de-linking of the supply of U.S. Dollars from U.S. Government control since an increasingly large proportion of dollar loans were being made geographically offshore from the U.S.

The Federal Reserve currently cannot have a money supply target because it cannot control the global eurodollar market, which is legally, geographically, and politically independent of the U.S., so it has to try to influence the money market via interest rate targets.

As the U.S. banks advanced their internationalization in the 1960s, some jurisdictions decided to capitalize on this by designing regulations to attract them. The City of London was a first mover here. Despite the Pound Sterling's declining relevance, London retained dominance as a financial center by becoming a hub for offshore dollars. Following this, Luxembough quickly created competitive regulations to attract international financial institutions seeking competitive taxation and a way to issue new financial products credibly in a stable jurisdiction.

In this context, Barletta thought Panama could become a competitive market. First, Panama is dollarized, so banking in USD is second nature and would be more convenient. Second, Panama is geographically close to the U.S., so business executives can easily commute to the company's branches in Panama. Thirdly, he believed that Panama could compete in terms of competitive tax policy, secrecy, and stability. Fourthly, because of the Panama Canal and Free Trade Zone, there are already natural perpetual customers for international banking products.

Barletta mentions in the interview that in designing the new banking law from Panama, he had some assistance from a banker who worked at Citi Bank and from the head of the central banking department at the International Monetary Fund. He noted that:

“we didn’t want a central bank, but we wanted to modernize the banking system to be in tune with the need for growth in the economy. So the objectives were to establish a system that could continue to nurture the growth of the economy” [my translation].

Once the law was written and approved in 1970 by the government, Barletta became the Chair of the National Banking Commission responsible for approving new banks in Panama. He also frequently traveled internationally to promote Panama as a new banking center after becoming the Minister of Economy and Planning in 1973. When asked what Omar Torrijos thought about these free-market-oriented banking laws, Barletta explained, “[Torrijos] left the economic part in our hands.”

As noted previously, before the 1970 Banking Law, Panama had very few banks, but by 1980, Panama had 125 banks because of Barletta and his teams. By 1975, International Monetary Fund economists had been signaling that Panama had risen to become a global center of eurodollars (what was then also called the “euro-currency”):

Banks active in the Euro-currency market operate from widely dispersed banking centers. London is still the main center of the offshore banking business. However, since 1970 its share in the total has declined, mainly to the advantage of the Bahamas, Singapore, Panama, and Beirut.

In a 1985 review of Panama’s international banking center, an IMF economist described the center's growth as “remarkable.” Between 1970 and 1980, foreign deposits in Panama grew at a “phenomenal” average annual rate of 65%, compared to the previous decade's 12% average annual growth rate.

This situation significantly increased the domestic exposure of commercial banks in Panama. This exposure can be seen in the sharp rise of banks' net foreign short-term liabilities. These liabilities were relatively modest in earlier decades: US$28.0 million from 1950-60 and US$66.0 million from 1961-70. However, they skyrocketed to US$933.0 million during 1971-80. This substantial influx of capital allowed Panama's banking system to expand credit to private and public sectors rapidly.

Barletta’s plan to anchor domestic credit creation via internationalization instead of using central bank discretionary policy was proven to work. This is essential to Panama’s “monetary policy” with a dollarized economy. Panama has never had a Balance of Payments crisis or general systemic liquidity crisis because of its immense excess liquidity. Moreover, since most banks have an international headquarters, they can quickly source liquidity from their headquarters or related entities if needed. Panama really became a small dollar liquidity lake tethered (without obstruction) to the giant ocean of global dollar liquidity — or what can be called absolute financial integration.

Torrijos died in 1981, and 1984 Barletta was elected the civilian President of Panama. President Barletta attempted to carry out further free-market-oriented reforms of the broader Panamanian economy, but significant popular resistance forced him to scale down the reforms. In another interview, Barletta observed that “perhaps I was too impatient” when he attempted to get through the free-market-oriented reforms.

At this time, Panama was still ultimately controlled by the military junta, now led by Manuel Noriega.

In September 1985, the military junta ordered the torture and beheading of Hugo Spadafora, a regionally well-renowned Panamanian doctor turned counter-revolutionary who was critical of Noriega and the dictatorship. After the brutal murder of Dr. Spadafora, A few days later, President Barletta, while away in NYC attending the UN General Assembly, announced that he would set up a commission to investigate the crime credibly. When he returned to Panama, Noriega summoned him and forced him to resign.

The 1980s were a turbulent decade for Panama. The global crisis of ‘82 and Barletta's expulsion in ’85 created concern for international banks, as Panama's stability and credibility became questionable. This led to the departure of several international banks. Noriega’s dictatorship intensified and worsened. This culminated in the U.S. invading Panama in December 1989 under ‘Operation Just Cause’ to remove Noriega.

The invasion was surprisingly successful, and democracy has remained stable in Panama ever since. In 1998, a new banking law was passed to modernize the banking center further and create a more sophisticated regulator—the Superindencia de Bancos de Panamá, of which Barletta was on the Board of Directors. The following year, in 1999, the Panama Canal was officially handed over to Panama's government from the U.S.

Recap and Look Forward

Panama’s metamorphosis into a regional and global financial hub can be traced back to Nicolás Barletta’s vision for national development. His free-market-oriented economic reforms, heavily influenced by his training at the University of Chicago, laid the foundation for Panama’s international banking center in a dollarized economy.

Barletta is woefully overlooked in the economics literature on Latin American development and should be classed similarly to the other Chicago Boys from Chile.

In the next post, I plan to describe the structure of Panama’s banking system to explain how monetary policy works without a central bank. This is relevant to the dollarization debate because it is clear to me that people do not realize how active a role the National Bank of Panama (Banco Nacional) plays in monetary operations (but not monetary policy) in the country.

Very interesting and well researched, thanks a lot

Another masterfully detailed piece. A fascinating read!!! 😉